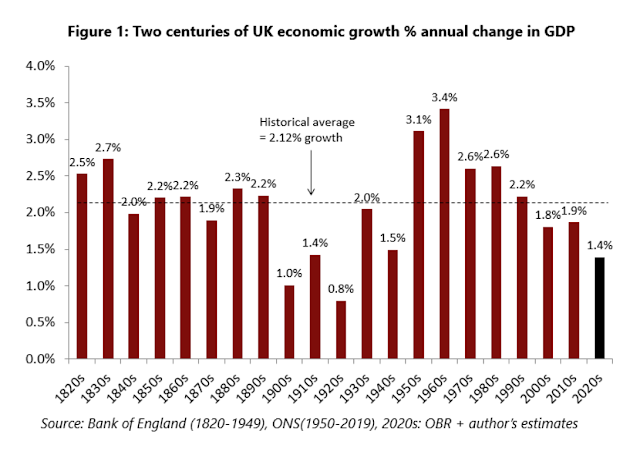

Earlier today, the Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, gave a speech at the Resolution Foundation outlining the nature of the Covid-19 crisis and the challenge that it poses for monetary policy. But as his speech progressed, it became clear that the Bank faces a much larger challenge. Covid-19 hit the UK economy at the end of a dismal decade. Returning to "where we were" before the pandemic won't be good enough. Just how dismal the 2010s were is evident in this chart from Andrew Sentance: Even before Covid-19 struck, average GDP growth was well below its historical average and heading downwards. The 2010s were, to put it bluntly, a decade of stagnation. The 2000s were slightly worse, but that was because they included the deep recession after the financial crisis, during

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: austerity, Brexit, COVID-19, GDP, growth, investment

This could be interesting, too:

Angry Bear writes GDP Grows 2.3 Percent

Nick Falvo writes Homelessness planning during COVID

NewDealdemocrat writes Real GDP for Q3 nicely positive, but long leading components mediocre to negative for the second quarter in a row

Stavros Mavroudeas writes COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Imperialism – Review of Radical Political Economics

Earlier today, the Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, gave a speech at the Resolution Foundation outlining the nature of the Covid-19 crisis and the challenge that it poses for monetary policy. But as his speech progressed, it became clear that the Bank faces a much larger challenge. Covid-19 hit the UK economy at the end of a dismal decade. Returning to "where we were" before the pandemic won't be good enough.

Just how dismal the 2010s were is evident in this chart from Andrew Sentance:

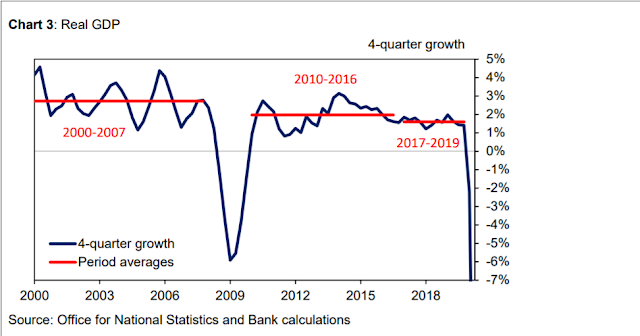

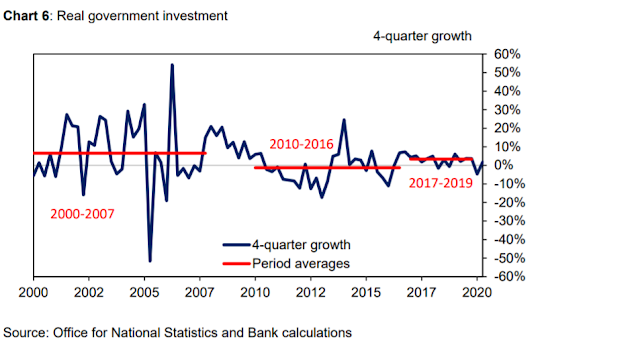

There's quite a lot of noise in the figures, particularly prior to the financial crisis, so the Bank of England has helpfully added lines showing average RGDP growth for three key periods: 2000-2007, 2010-2016, and 2017-19. It is evident that the average in each period is lower than in the one before. The growth rate appears to be trending downwards.

But let's look through those lines and see what the chart itself tells us. Firstly, and obviously, GDP growth was on average stronger before the financial crisis than afterwards. And it was also considerably more volatile. We don't know why, but one factor might be the light regulation of the financial sector at that time. Bank lending is known to be pro-cyclical, so variations in banks' appetite for risk might be expected to cause swings in the GDP growth rate. Since the financial crisis, the financial sector has been much more tightly regulated. This dampens the procyclicality of bank lending, so might reduce the volatility of GDP growth. But does it also dampen the average GDP growth rate?

Secondly, the post-financial crisis recovery tailed off quickly and GDP growth slumped to less than 1% in 2011-12. Was this solely because of the impact of the Eurozone crisis, or did the front-loaded austerity of the Coalition government play a part? In my view, an under-appreciated factor is the tax increases on energy in 2010-11, which combined with a sharp rise in oil prices to cause energy price rises of 20% or more for households and businesses.

The economy recovered to a post-crisis high by 2014. But then growth tailed off again. What caused this? And why has the GDP growth rate been pretty much stuck at a measly 1.5% since 2016?

Much of Bailey's speech is devoted to the economic reasons for this long slump. The political issues understandably didn't get an explicit mention, but they were there under the surface, and the French economist Helene Rey didn't hesitate to spell them out in her response. It is not just the Covid-19 crisis from which the UK economy must recover. And although the financial crisis threw a long shadow, it was not responsible for the GDP growth rate flatlining in 2017-19. That was caused by Brexit.

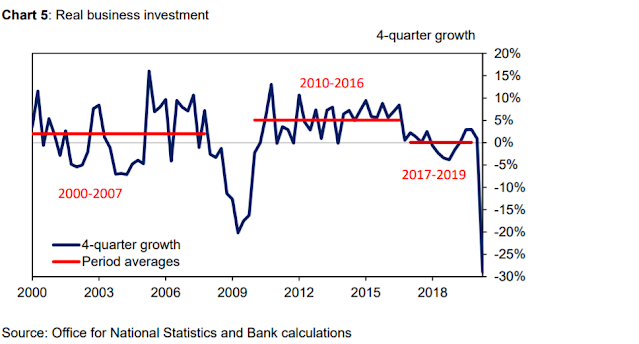

It has become taboo to say, or even imply, that the Brexit vote of 2016 was in any way negative for the UK economy. If the Bank of England governor had dared to say openly that the primary reason for four years of stagnation prior to the Covid-19 shock was investment collapse due to Brexit, he would have been accused of making political statements. But it is the truth.

Here's the evidence from Bailey's speech:

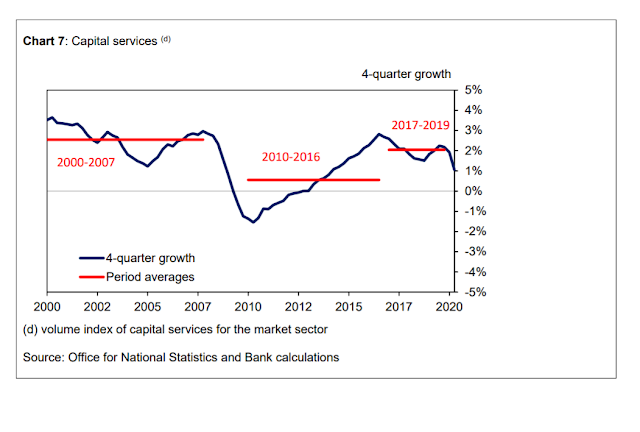

The effect of this weakness in investment can also be seen by looking at capital services – a measure of the value of the flow of services which are derived from the capital stock, including machinery, equipment, software, structures, and land improvements. This may better capture the drivers of supply growth than looking at growth in investment alone. It shows a sharp decline following the collapse in investment during the global financial crisis, and a subsequent recovery, which flattened off as a result of the weak investment in the period prior to Covid.

The chart actually shows that the recovery in capital services growth was partially reversed by the Brexit vote. But I guess that is too "political" for the Governor of the Bank of England to say openly.

Image: The Slough of Despond from Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan.