Is our biggest worry inflation? No, our biggest worry is a fall in employment, investment and income.Inflation is caused by the economy ‘overheating’. Wage and price inflation arises when economic activity (investment, employment, income) exceeds the capacity of the economy. Put simply, inflation most often arises in conditions of full employment, when incomes are high and rising and when investment in new jobs, speculation and the creation of new assets, surges. Many point to the 1970s as an example of high inflation, which indeed it was. In 1970 at the end of a period of Labour government, inflation was at 5%. Under reckless financial deregulation – defined as Competition and Credit Control – and instigated by Edward Heath’s Treasury Minister, Anthony Barber, the availability of largely

Topics:

Ann Pettifor considers the following as important: Article, Employment, GDP & Economic Activity, Inflation & Deflation

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

T. Sabri Öncü writes Argentina’s Economic Shock Therapy: Assessing the Impact of Milei’s Austerity Policies and the Road Ahead

T. Sabri Öncü writes The Poverty of Neo-liberal Economics: Lessons from Türkiye’s ‘Unorthodox’ Central Banking Experiment

Ken Houghton writes Just Learn to Code

Is our biggest worry inflation? No, our biggest worry is a fall in employment, investment and income.

Inflation is caused by the economy ‘overheating’. Wage and price inflation arises when economic activity (investment, employment, income) exceeds the capacity of the economy. Put simply, inflation most often arises in conditions of full employment, when incomes are high and rising and when investment in new jobs, speculation and the creation of new assets, surges.

Many point to the 1970s as an example of high inflation, which indeed it was. In 1970 at the end of a period of Labour government, inflation was at 5%. Under reckless financial deregulation – defined as Competition and Credit Control – and instigated by Edward Heath’s Treasury Minister, Anthony Barber, the availability of largely deregulated credit was massively expanded. (Duncan Needham outlines the history in Britain’s Money Supply Experiment, 1971-3. ) At the same time PM Edward Heath, encouraged by the OECD made a “dash for growth” central to his premiership. (For more on this see Geoff Tily on ‘The Growthmen”). Heath’s overt policy expanded economic activity (in property speculation, consumption and ‘secondary banking’) and caused inflation to peak in 1975 at 26%.

The experience of the 1970s – often deliberately and wrongly blamed on trades unions and labour – confirms the theory outlined above.

Deflation is caused by a contraction of the economy – typically by an excessive amount of spare capacity, represented by low levels of productive investment; high levels of unemployment and low levels of income. Conditions during the period after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) (2007-20) show that deflationary pressures were a feature of both the British and European economies, but also the global economy.

Is inflation about to rear its ugly head again? To answer that question we have to ask if economic conditions have changed so much that the economy has hit full capacity? Clearly not. There is still enormous ‘slack’ in the economy. In the words of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Report of February, 2021:

Overall, there is judged to be a material amount of spare capacity in the economy at present.

This comes as no surprise. The British economy is in a deep coma – and remains critical, even while on governmental life support. The Bank of England expects UK GDP to fall in 2021 Q1, and to be weaker than projected three months ago – about 12% below its 2019 Q4 level.

It will take a long time to recover from such a unique and devastating slump in economic activity, and from the traumas of the pandemic, of Brexit and of the digitisation of job-rich retail sectors.

But even while the economy is comatose, there are enough ‘clinical signs’ emerging from the structural changes brought about by these traumas to indicate that recovery will be slow and protracted.

First, most importantly: investment, which has over the last year both fallen and then partially recovered. According to the ONS the first lockdown in March, 2020 led to a 22.1% fall in business investment, between Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2020 and Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2020. Excluding the effects of a re-classification in 2005, this was the largest quarterly fall on record.

The easing of lockdown restrictions in Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2020, led to a rise of 14.5% in business investment which hit another record – for the largest quarterly increase.

However, though investment has grown since both its record fall and rise, it is still 10.3% below where it was at the end of 2019. As the ONS reminds us:

The higher levels of economic uncertainty are potentially having a more pronounced effect on the willingness of firms to undertake investment.

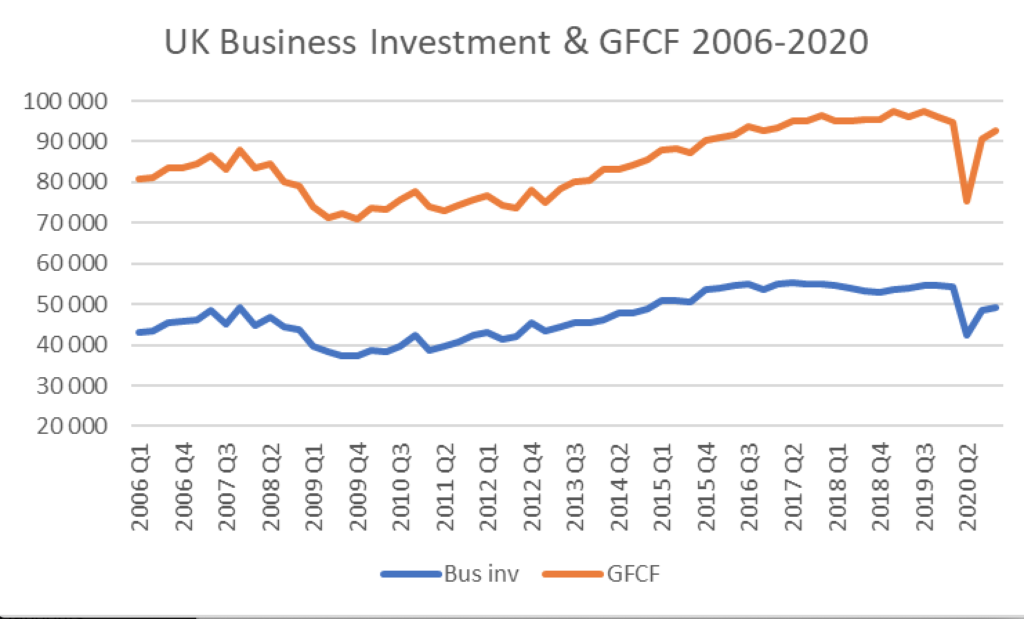

But firms have been reluctant to increase investment for many years, as the chart below, based on ONS data, shows:

Business investment fell by nearly 10% after the GFC, and because governments deliberately refused to compensate for that fall by increasing public investment, ‘austerity’ was a feature of the post-GFC British economy. Austerity worsened economic conditions for firms, so investment was tentative, rising only slowly after 2011. With the 2016 Brexit vote, business investment stalled.

If the Boris Johnson government resorts to ‘austerity’ and contracts public investment, then post-pandemic conditions are likely to cause firms to remain timid and cautious.

The authorities lack confidence that investment will recover and rise to expand economic activity after the lock-down exit. Although the Bank of England expects private sector investment to rise in 2021, as sales recover and uncertainty declines, it predicts the rise will lag consumer spending. The Bank worries rightly, that

Lower investment could reduce innovation and weigh on the productive capacity of the economy over time. The UK’s withdrawal from the EU is also projected to have a persistent effect on supply, as trade barriers result in lower cross-border trade, which in turn dampens investment and employment.

Low levels of investment are matched by low levels of employment. In January this year, despite government support, the number of employee jobs was down by more than 800,000 over the year, as the Resolution Foundation reports. 4.5 million workers are on furlough – with no certainty as to their futures. Long-term unemployment (those unemployed for 12 months or more) stood at 357,000 in the three months to November 2020, up from 241,000 in the three months to May.

To paraphrase Warren Buffett: only when the furlough ‘tide’ goes out will we discover who has been swimming naked – which firms have gone bust and what proportion of those 4.5 million workers hang on to their jobs. The fear is that many companies will want to repair balance sheets and pay down debts to government by opting for redundancies and job losses. That is when the threat of mass unemployment will rise, disrupting the futures of millions, including a whole generation of young people (16-24) most vulnerable to confidence-sapping job losses and de-skilling.

Unemployment and precarious employment will further contract economic activity – and shrink the incomes of workers and firms. This fall in incomes will come on top of the dramatic fall in incomes caused by the pandemic. As Chris Marsh, aka The General Theorist, explained, the pandemic’s biggest shock was not the collapse in consumer spending, but a sudden and dramatic “shortfall of effective income.”

Our community—and the structure of credits and debits within society—is underpinned by an anticipated flow of income between economic actors. But these flows can be no longer sustained due to a temporary, vexing, and in too many cases devastating virus.

The Job Retention Scheme (JRS) helped maintain the incomes of a small proportion of the population, and of very few firms. But many millions failed to qualify for government support. As Guy Standing argued in the FT in April, 2020, the worst feature of the JRS:

is its distributional design, in what I predict will turn out to be one of the most regressive labour market policies ever. Someone with a salary of £2,500 per month will receive £2,000 a month. Someone on £1,000 will receive £800. Someone in the precariat – on a zero-hours contract, for example, or reliant on tips to make up low wages – will receive very little.

The shock of the pandemic’s shortfall of income hit the labour force after a period during which British workers had experienced a prolonged wage squeeze, one the TUC described as “the longest and most costly wage squeeze since 1822.” Where new jobs were created, they tended to be in insecure, low-paid, gig economy-type employment. As a consequence, many borrowed to supplement their income, and are left with unpayable debts.

Low and falling incomes compounded by the deflationary impact of debt, will, as before, quickly lead to the contraction of economic activity and to low and falling inflation.

Given the shocks and scars endured by the private sector, post-pandemic investment and job creation is likely to be timid and cautious. Unless the UK Treasury deliberately expands activity by investing in the creation of new, skilled, green and high-income jobs, then we can confidently expect incomes – and inflation – to fall further.

Inflation will however persist in one part of the economic forest: that part occupied by the wealthy. For reasons that can only be deemed ideological, asset price inflation has caused no alarm in the minds of most mainstream economists, and is largely played down by politicians, central bankers and treasury officials. As this goes to press, the UK Treasury is floating a plan to throw even more money at existing assets – including old Victorian properties in cities like London – by offering guarantees for housing loans of up to £600,000 to bankers and developers. As I explained back in January, 2018, as more finance is aimed at existing assets, the value of properties (including new housing developments) will inflate, and enrich the already-rich. At the same time it will place homes beyond the reach of young, low-income families most in need of a roof over their heads.

This form of asset price inflation, and its impact on inequality, economic and social instability, will not be considered a crisis at all by the economics profession. Public perception might differ. Many will see this form of inflation for what it is: after a catastrophic economic event, yet another windfall bonus for the 1%.

End.