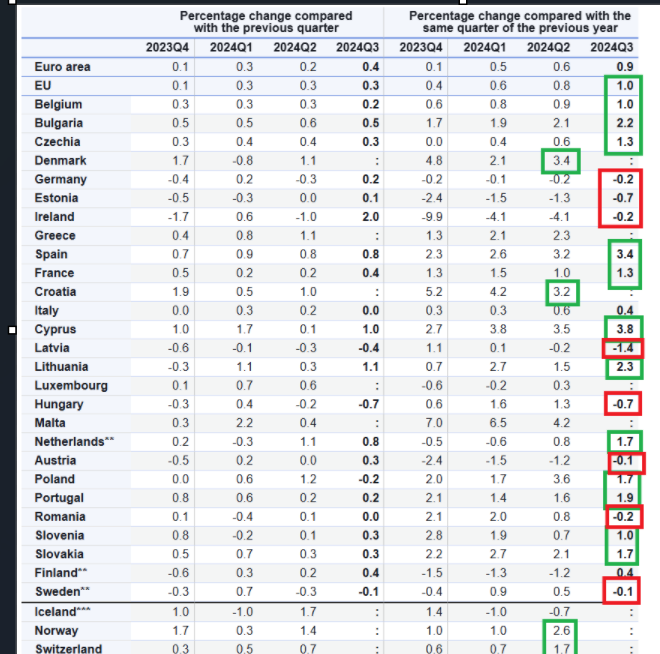

Eurostat published new data on employment in Europe. Average employment growth is +0,9%. The average hides stark differences. A Germany-centered core consisting of Germany, Austria, Sweden, Estonia, Finland, and Hungary shows declines. Surprisingly, it excludes Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands. The South does better. Countries like Portugal, France, Greece, and, especially, Spain post above-average increases. But unemployment in these countries is still high (over 5%), even when EU long-term unemployment hit a historical low (1,9%, Eurostat, series starts in 2005). Table 1. Employment growth in Europe. Source. How come? Labour market participation rates of men went down after about 1970, but this was more than compensated by increasing participation rates of women.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: demographics, economy, Employment, Europe, Finance, news, Uncategorized, Unemployment

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Eurostat published new data on employment in Europe. Average employment growth is +0,9%. The average hides stark differences. A Germany-centered core consisting of Germany, Austria, Sweden, Estonia, Finland, and Hungary shows declines. Surprisingly, it excludes Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands. The South does better. Countries like Portugal, France, Greece, and, especially, Spain post above-average increases. But unemployment in these countries is still high (over 5%), even when EU long-term unemployment hit a historical low (1,9%, Eurostat, series starts in 2005).

Table 1. Employment growth in Europe. Source.

How come? Labour market participation rates of men went down after about 1970, but this was more than compensated by increasing participation rates of women. According to Eurostat, de facto pension ages are increasing by about one month per year, which leads to an increase in the labour force. Also, immigration swelled the ranks of European people who were able and willing to work, especially in Spain. Labour market participation rates of men went down after about 1970, but this was more than compensated by increasing participation rates of women. According to Eurostat, de facto pension ages are increasing by about one month per year, increasing the labour force. Also, immigration swells the ranks of the number of people who are able and willing to work. Together, these factors caused a HUGE increase in the labour force after around 1995. When 2009 the Great Financial Crisis struck, EU economists did not grasp the chance to re-employ these people but stated that anything below 20% unemployment would increase inflation in, for instance, Spain. Morons. This means that, fifteen years after the crisis and despite massive job growth, Spanish unemployment is still high.

What to make of this? The scramble for people has started. After 1965, the German birth rate began to plummet, and other countries rapidly followed. ´Natural´ population growth morphed into natural decline. This led, because of migration, not to a decrease in the resident population of Germany (or, another example, the Netherlands). However, Greece and Poland’s populations declined by around 7% – largely because of out-migration. The Bulgarian population even decreased by a third. The big winner: Spain. Remarkably, despite unemployment rates of over 20%, the Spanish population did not decline after the Great Financial Crisis. Around 2000 the Spanish population was about as large as the Polish population. At this moment, it is about one-third larger.

Graph 21 The rapidly growing population of Spain. Source.

A less technocratic way to state this: during ´les trentes glorieuses´, the high growth period between 1952 and 1980, many became unemployable because of inadequate education, skills, or capital. An example is the millions of European peasants who could not afford to mechanize their farms (if you regret mechanization of agriculture, please manually harvest your potatoes on a rainy November day for ten hours in a stretch). Retirement ages went down, and many subsidies were invented to keep the unemployable afloat (which prevented poverty). These policies have been and are being rolled back as the number of unemployable declined. We´re entering a period of labour and people shortages. Countries have to provide well-paying jobs to keep and attract people and reasonable social security to keep them. Or, what is happening already, countries might force people. The draft, which is making a comeback, is an example. North-Korean drafted mercenaries in fighting in Ukraine might be a very 21st-century event.