Summary:

Guest post by Ari Andricopoulos It is difficult to read the history of inter-war Europe and the US without feeling a deep sense of foreboding about the future of the Eurozone. What is the Eurozone if not a new gold standard, lacking even the flexibility to readjust the peg? For the war reparations demanded at Versailles, or the war debts owed by France and the UK to the US, we see the huge debts owed by the South of Europe to the North, particularly Germany. The growth model of the Eurozone now appears to be based largely on running a current account surplus. Competitive devaluation is required to make exports relatively cheap. While this may have been a very successful policy for Germany during a period of high economic growth in the rest of the world, it cannot work in the beggar-thy-neighbour demand-starved world economy of today. As I've explained elsewhere, reasonably large government deficits are very important for sustainable economic growth. However, in the Eurozone this is prohibited both by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and by the fear of losing market confidence in the national debt. At the same time credit growth for productive investment is constrained by weak banks and Basel regulation. And the Eurozone as a whole is already running a large current account surplus; the rest of the world will not allow much more export-led growth.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: austerity, EU, euro, Eurozone, inflation, sovereign debt, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Guest post by Ari Andricopoulos It is difficult to read the history of inter-war Europe and the US without feeling a deep sense of foreboding about the future of the Eurozone. What is the Eurozone if not a new gold standard, lacking even the flexibility to readjust the peg? For the war reparations demanded at Versailles, or the war debts owed by France and the UK to the US, we see the huge debts owed by the South of Europe to the North, particularly Germany. The growth model of the Eurozone now appears to be based largely on running a current account surplus. Competitive devaluation is required to make exports relatively cheap. While this may have been a very successful policy for Germany during a period of high economic growth in the rest of the world, it cannot work in the beggar-thy-neighbour demand-starved world economy of today. As I've explained elsewhere, reasonably large government deficits are very important for sustainable economic growth. However, in the Eurozone this is prohibited both by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and by the fear of losing market confidence in the national debt. At the same time credit growth for productive investment is constrained by weak banks and Basel regulation. And the Eurozone as a whole is already running a large current account surplus; the rest of the world will not allow much more export-led growth.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: austerity, EU, euro, Eurozone, inflation, sovereign debt, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Matias Vernengo writes Serrano, Summa and Marins on Inflation, and Monetary Policy

Angry Bear writes Voters Blame Biden and Harris for Inflation

Lars Pålsson Syll writes How inequality causes financial crises

Matias Vernengo writes Inflation, real wages, and the election results

Guest post by Ari Andricopoulos

It is difficult to read the history of inter-war Europe and the US without feeling a deep sense of foreboding about the future of the Eurozone. What is the Eurozone if not a new gold standard, lacking even the flexibility to readjust the peg? For the war reparations demanded at Versailles, or the war debts owed by France and the UK to the US, we see the huge debts owed by the South of Europe to the North, particularly Germany.

The growth model of the Eurozone now appears to be based largely on running a current account surplus. Competitive devaluation is required to make exports relatively cheap. While this may have been a very successful policy for Germany during a period of high economic growth in the rest of the world, it cannot work in the beggar-thy-neighbour demand-starved world economy of today.

As I've explained elsewhere, reasonably large government deficits are very important for sustainable economic growth. However, in the Eurozone this is prohibited both by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and by the fear of losing market confidence in the national debt. At the same time credit growth for productive investment is constrained by weak banks and Basel regulation. And the Eurozone as a whole is already running a large current account surplus; the rest of the world will not allow much more export-led growth. Helicopter money would be a solution, but politically this is a long way away. Summing up, if economic growth cannot be funded by government deficits, private sector debt, export growth or helicopter money it is very difficult to see where nominal GDP growth can come from.

In a way, this can be seen as a Prisoner’s Dilemma. Every country knows (or should know) that if all states provided fiscal stimulus, the Eurozone would benefit from more economic growth. However, for any individual state, a unilateral fiscal boost would increase their own government debt whilst giving a fair amount of the GDP growth to other states (because some of the stimulus would go to increasing imports from the other nations). And if all others provide stimulus, then it is in an individual state’s interest to take the benefit of the other states’ stimulus, and become more competitive versus the rest.

The huge imbalances created by the fixed exchange rate system, described in this great piece by Michael Pettis, are still there. The enormous current account surplus built up by Germany makes it extremely difficult for the less competitive countries to run a current account surplus. The only way for this to happen, without German inflation, is by internal devaluation; a long and painful process to lower wages, which may succeed in achieving a current account surplus, but only at the expense of shrinking the economy. The debt owed to the creditor nations therefore gets larger in real terms. In the end, the debts owed by the South to the North are unpayable without the Northern countries running a current account deficit and using the savings built up during the amassing of the surplus to buy goods from the South. But the Northern surpluses are only getting bigger.

On top of this, all countries in the Eurozone are committing the "original sin" of borrowing in a foreign currency. This can only be a time bomb, waiting to devastate Europe.

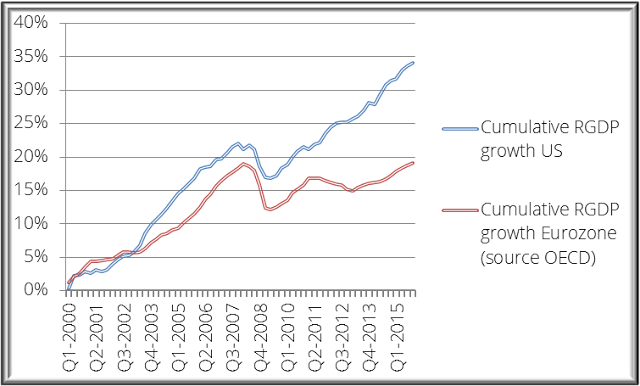

The effect of all of this becomes clear when comparing GDP growth in the Eurozone to that of the USA. In the period up to 2008, before the problems of the Eurozone structure became apparent, the growth was pretty comparable. This is to be expected with two similarly developed large blocs. The trend growth is driven by innovation and there is enough money flowing through the system to support it. After 2008, however, is a different story. The growing gap between the two economies is largely due, in my opinion, to the existence of the Euro.

My prediction, as things stand at the moment, is that the ECB will never be able to have positive interest rates again. Growth will only deteriorate from here and eventually the currency union will have to break up. I do hope that I am wrong on this and that a political solution can be found.

Having said all of this, I believe that there is a solution that, given the political will (admittedly this is a big caveat) could make the Euro a workable currency. It consists of three parts, and the idea came from a Twitter discussion with Frances Coppola a few months ago, following this post by Simon Wren-Lewis on using inflation as a metric for determining how large the government deficit/surplus should be.

A three-point plan

1) The ECB should make an implicit guarantee of all Eurozone government debt, just as the Bank of England, the BoJ or the Federal Reserve do.

They should state that all interest payments by all states will be approximately the same, ie. no member state has credit risk. This interest rate is thus a reflection of nominal growth rates across the Eurozone, and not of the individual default risk of any member state.

This is important because otherwise countries with default risk must borrow at higher rates, thus worsening their already (by definition) bad situation. This avoids the potential death spiral that hit Greece when the market lost confidence.

It also removes the risk to the banking system caused by holding national debt with default risk. Currently a teetering bank and teetering government could pull each other over the edge of the cliff.

2) The stability and growth pact should be scrapped and replaced with a new one that is fit for purpose. In a more appropriate stability and growth pact, the fiscal mandate of all member states is purely to target inflation. It does not matter if a government has a budget surplus of 5% or a budget deficit of 5%; all that matters is that it hits the inflation target.

Punishments, in the form of large fines, should be given to any government that strays too far from its cumulative target, on either side of the target, as it is a crucial part of maintaining growth and balance in the economy. Any state running too high a deficit will get higher growth rates, but they will add to the inflation of the Eurozone and thus devalue the currency for everyone else. Any state running too low a deficit will get a competitive advantage that takes demand from the other states and gives them a current account surplus at the expense of the others.

3) Although the average inflation across the Eurozone can remain at 2%, this inflation target should be different for different members. A country running a large relative current account surplus with a large accumulation of net foreign assets needs to run a higher inflation rate, say 3%. This would be set each year in advance by an independent formula. A country with large debts should run a lower inflation rate, say 1%.

The targets would be cumulative. So if a country needed to run 3% a year for 3 years and in the first two they only hit a 2% inflation target, then the target in the third year would be just over 5%. Likewise if they were getting 4% inflation for the first two years the target would be just over 1% in the third year.

This would mean that over the years, the (long under-rewarded) workers in the creditor countries would get wage rises and have more and more buying power, enabling them to buy more goods from the debtor countries. The increase of buying power means the previously accumulated savings by people in the creditor countries now flow back the other way. This makes it possible for debtor countries to be able to repay the creditor countries. Balance is restored.

In the past, the South consumed more than they produced, using money borrowed from the North to fund their consumption. In this new regime, the South would be effectively be working their debt off for the North.

This is far better than the current situation where the South is not working and the North is not getting paid.

This does not preclude the running of a current account surplus. If this is to be the desired policy, then (probably through currency manipulation) it could still be achieved. The difference would be that the surplus would be balanced across the whole Eurozone, and achieved at the expense of the rest of the world rather than other Eurozone members.

Summary

This three-point plan would address all of the main structural problems of the Eurozone.

It addresses the imbalances between nations by using inflation to force nations to equalise their competitiveness. This balance is important because it allows money to flow both ways, meaning that debts are less likely to arise and, if they do, can be repaid without creating hardship. These imbalances are the cause of the previous Eurozone crises and are responsible for Greece’s current predicament. Point 3 of the plan prevents them from building up.

It solves the Prisoner’s Dilemma problem above because it forces coordination of fiscal stimulus – it does not allow one country to take advantage of the others to boost its own competitiveness. It means that Eurozone nations would no longer be undercutting each other for competitiveness.

It removes default risk, allowing governments to run large enough deficits to allow nominal GDP growth. It removes fear of borrowing so that governments can invest in projects that will improve future growth. It means that governments would no longer need to pay credit spreads to bond-holders; a cost no sovereign currency government normally has to pay. And it removes the sword of Damocles from above the head of every debtor nation. No longer would economic survival be a case of "there but for the grace of the bond markets go I".

It does so without allowing any country a free pass. One nation may have larger debt than another, but not enough to cause the inflation so feared by Germany in particular. And because of the differential inflation rule, higher debt countries will naturally be able to pay off that increased debt.

And there are no fiscal transfers between countries. These, for obvious reasons, are very unpopular between nations and can cause a lot of resentment. Every time a country defaults in the current system, transfers are made and rifts between nations are built up. This is very damaging to European unity and can be avoided.

But the biggest benefit of all is that it would mean higher economic growth for every nation in the Eurozone.

It is my wish that we can find the political will for this type of solution. Surely this is the true meaning and spirit of European cooperation; working together to have a better outcome for all.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Ari Andricopoulos is a principal at Dacharan Advisory AG, an investment manager. He has a Ph.D in Financial Mathematics from Manchester University and has published in various academic finance journals. His personal blog is Notes On The Next Bust. Follow him on Twitter @ari1601.

Image from Carlos Latoff via www.occupy.com, with thanks.

Related reading: