The Governor of the Bank of England's opening remarks at the release of today's Financial Stability Report were stark: At its March meeting, the FPC judged that “the risks around the referendum [were] the most significant near-term domestic risks to financial stability.” Some of those risks have begun to crystallise. The Governor was admirably calm and balanced in his press conference. But nevertheless there was a degree of schadenfreude about his remarks. Prior to the referendum, the Bank of England was severely criticised by the Leave campaign for scaremongering. It was accused of overstating the economic risk in order to support the Remain campaign. But it is already clear that the Bank's analysis was accurate, as least as far as the near-term risks are concerned.The principal risks identified by the Bank of England are threefold. Firstly, the financing of the UK's current account deficit is coming under pressure as inward investment flows slow down or reverse. Secondly, the UK's commercial real estate market - already overstretched and far too reliant on external funding - is suffering severe outflows and sharp valuation adjustments. And thirdly, over-indebtedness in the household sector raises the possibility of an aggregate demand shock and pressure on the housing market. Yippee.The most obvious indication of the pressure on the current account is the fall in sterling.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Brexit, currency, Debt, property, recession, UK

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

Matias Vernengo writes Elon Musk (& Vivek Ramaswamy) on hardship, because he knows so much about it

NewDealdemocrat writes What to look for if housing construction does forecast a recession

Robert Skidelsky writes Speech in the House of Lords Conduct Committee: Code of Conduct Review – 8th of October

The Governor of the Bank of England's opening remarks at the release of today's Financial Stability Report were stark:

At its March meeting, the FPC judged that “the risks around the referendum [were] the most significant near-term domestic risks to financial stability.” Some of those risks have begun to crystallise.The Governor was admirably calm and balanced in his press conference. But nevertheless there was a degree of schadenfreude about his remarks. Prior to the referendum, the Bank of England was severely criticised by the Leave campaign for scaremongering. It was accused of overstating the economic risk in order to support the Remain campaign. But it is already clear that the Bank's analysis was accurate, as least as far as the near-term risks are concerned.

The principal risks identified by the Bank of England are threefold. Firstly, the financing of the UK's current account deficit is coming under pressure as inward investment flows slow down or reverse. Secondly, the UK's commercial real estate market - already overstretched and far too reliant on external funding - is suffering severe outflows and sharp valuation adjustments. And thirdly, over-indebtedness in the household sector raises the possibility of an aggregate demand shock and pressure on the housing market. Yippee.

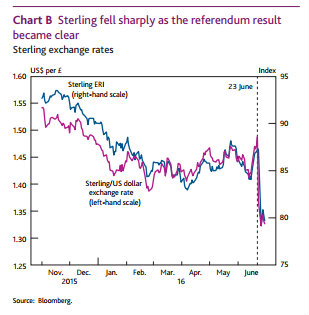

The most obvious indication of the pressure on the current account is the fall in sterling. Sterling fell sharply on the night of the referendum results, as the Bank of England's chart shows:

Sterling has fallen further since, though not so sharply. It is now at its lowest level since 1985. Though it is worth putting this fall in context:

Maybe it is a little too soon to panic about the falling value of the pound.

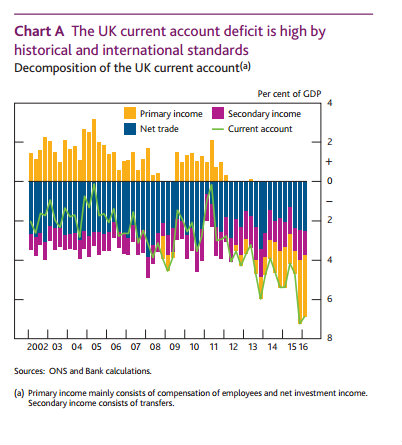

But worries about the UK's current account deficit are legitimate. It is historically large, as can be seen from this chart:

Primary income switched from surplus to deficit as the Eurozone crisis started, and has gone deeper into deficit since. The ONS notes that although both receipts and payments have fallen, receipts have fallen by considerably more than payments - hence the primary income deficit. The reason is the falling rates of return on overseas investments:

The decline in credits over this period largely reflects continuing deteriorations in rates of return, which have fallen from a peak of 7.7% in 2011 to 5.0% in 2014, and have fallen further in 2015 to 4.8%. Annualised rates of return for Quarter 1 2016 indicate a further decline in the rate of return, having fallen to an estimated 3.0%.So the large deficit on primary income is due to poor investment performance elsewhere in the world - in particular, in Europe. Foreigners receive better rates of return in Britain than Brits do abroad. This is actually a sign of success. Our economy is doing better than theirs, so rates of return are higher - and that attracts inward investment. FDI and portfolio investment flows are very important to the UK.

But they are also a risk factor. If foreigners suddenly withdrew their investments, there would be a sharp correction to the current account - what we know as a "sudden stop". As the UK issues its own floating currency, this would cause sudden sharp devaluation, with (since the UK is an import-dependent economy) obvious implications for inflation. Since the UK runs a sizeable government deficit, which (in the absence of a domestic private sector surplus) is financed by those inward investment flows, it would also cause a fiscal crisis. And it would additionally cause a private sector debt crisis, since the flows also finance corporate investments, notably in commercial real estate. In short, the UK is terribly dependent on external capital flows for its economic and financial stability. Hence the watchful eye on sterling and the worry about the current account.

There is no sign as yet of anything as disastrous as a "sudden stop". In fact the fall in sterling experienced so far should be helpful to exporters (I have to declare an interest here - much of my income is in US dollars, so I have effectively had a pay rise!). But the absence of crisis does not make the shifting pattern of investment flows caused by the Brexit shock "beneficial". Closing a current account deficit by ruining the attractiveness of the economy to investors is not clever.

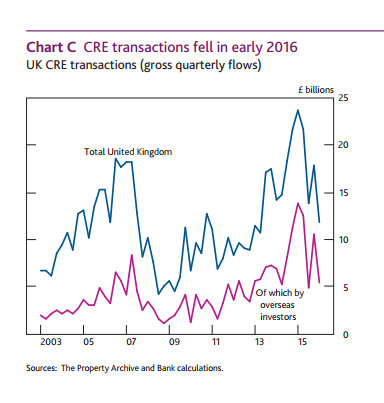

The commercial real estate market has been showing signs of strain since the beginning of the year. As the Bank of England's chart shows, foreign inflows of capital fell by almost

50% in the first quarter of 2016:

But the vote itself has had a dramatic effect. Share prices of investment funds have fallen sharply. Closed funds simply have to weather the storm, though they might close their doors to new investors. But open-ended funds face damaging runs and the possibility of fire sales. Yesterday, Standard Life announced it was suspending trading in its open-ended CRE fund. And today, M&G and Aviva followed suit.

Open-ended CRE funds are highly illiquid (it is not easy to sell office blocks and shopping centres at short notice), yet they offer redemption on demand to investors. This is maturity transformation on an even more extreme scale than banks, and these funds are consequently vulnerable to severe liquidity crises. Yet they do not have any form of liquidity support. Trade suspension is thus a necessary circuit breaker, and it is built into the terms and conditions of the funds. It is roughly the equivalent of a bank closing its doors to stop a bank run.

There is clearly going to be a severe correction in CRE prices. How damaging this will be to the economy depends on the impact on banks. Worryingly, it appears that UK banks - particularly smaller ones - are significantly exposed to CRE. But the Bank of England insists that it has covered all bases in its stress tests, so the banks should be able to absorb CRE losses without falling over. We shall see.

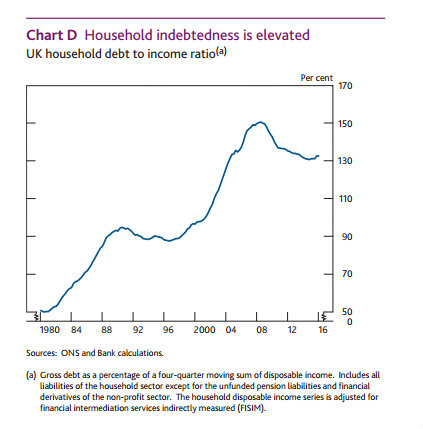

The third risk is one that I have persistently warned about. There is already evidence that the Brexit shock is causing people to delay spending and investment decisions. If this continues, then we can expect a significant economic slowdown, leading to real wage cuts and rising unemployment. Under such circumstances, high household indebtedness is a serious economic risk. And the UK's households have not significantly deleveraged since 2008. They still have far too much debt:

The Bank of England observes that highly-indebted households tend to cut back spending very hard when their incomes fall, preferring to honour their debts at the expense of their lifestyles. This can seriously reduce aggregate demand. And buy-to-let investors faced with interest rate rises may choose to sell out, causing house prices to fall and worsening the position of marginal borrowers. There is a risk of a self-reinforcing debt deflationary spiral developing, though tighter lending restrictions imposed in recent years may help to dampen these procyclical effects.

The market is already pricing in interest rate cuts, though the Governor refused to be drawn on what form these would take: he dislikes negative rates, not least because of the risk they pose to building societies, so maybe the preferred instrument will be some form of QE. And the Bank of England has relaxed countercyclical capital buffer requirements for banks to encourage them to keep lending - though the Governor admitted that demand for loans would probably fall.

But realistically the Bank cannot entirely protect the economy from the toxic combination of over-indebtedness and the Brexit shock. As the Governor said, all the indicators are that the UK faces a significant downturn. We are seeing falling stock prices on the FTSE 250 (though not the globally-focused FTSE 100), downwards pressure on gilt yields and a flattening yield curve. These are leading indicators of recession. To be sure, the UK might have been facing a slowdown anyway. But if so, the Brexit vote will make it much worse.

However, recessions don't last forever, and it is entirely possible that once the UK is completely disentangled from the EU, investment will return and the UK will come "roaring back". But how long this will take is impossible to tell. The patient won't die, but it could be decades before it is fully recovered.

In the long run, Britain may once again become a vibrant, world-beating economy. But as Keynes said, in the long run we are all dead. Particularly those who voted for this wholly unnecessary surgery, who are by and large the old. They will die: but the young will bear the scars.

Related reading:

The snake oil sellers

Who is really to blame for Brexit?

Image courtesy of The Telegraph.