I can't resist this. Blithely ignoring the utter mess he and his developers have managed to make of the cryptocurrency Ethereum, Vitalik Buterin has written a post on inflation and monetary policy. Wow. Is there no end to his talents? In this case, there is most definitely an end. Economics 101 is the end, pretty much. I don't claim to be the world's greatest economic expert - not by a LONG way - but the errors in this piece leapt out at me. Firstly, inflation. Here is Buterin on inflation: The primary expense that must be paid by a blockchain is that of security. The blockchain must pay miners or validators to economically participate in its consensus protocol, whether proof of work or proof of stake, and this inevitably incurs some cost. There are two ways to pay for this cost: inflation and transaction fees. Currently, Bitcoin and Ethereum, the two leading proof-of-work blockchains, both use high levels of inflation to pay for security; the Bitcoin community presently intends to decrease the inflation over time and eventually switch to a transaction-fee-only model. Inflation? Really? The cryptocurrency whose adherents promote it as the world's greatest ANTI-inflationary currency is suffering from inflation? Surely not!Definitely not. Let's remind ourselves of the economic definition of inflation.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Bitcoin, inflation, Interest rates, security

This could be interesting, too:

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Matias Vernengo writes Serrano, Summa and Marins on Inflation, and Monetary Policy

Angry Bear writes Voters Blame Biden and Harris for Inflation

merijn knibbe writes The incredible cost of Bitcoin.

The primary expense that must be paid by a blockchain is that of security. The blockchain must pay miners or validators to economically participate in its consensus protocol, whether proof of work or proof of stake, and this inevitably incurs some cost. There are two ways to pay for this cost: inflation and transaction fees. Currently, Bitcoin and Ethereum, the two leading proof-of-work blockchains, both use high levels of inflation to pay for security; the Bitcoin community presently intends to decrease the inflation over time and eventually switch to a transaction-fee-only model.

Definitely not. Let's remind ourselves of the economic definition of inflation. Since Buterin seems to like referencing Wikipedia, this is Wikipedia's definition:

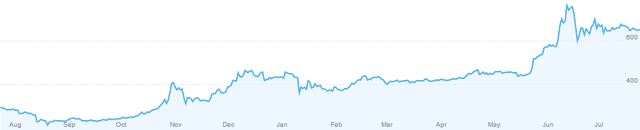

In economics, inflation is a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. When the price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money - a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy.....The opposite of inflation is deflation.So, if Bitcoin is inflating, it should be buying less of whatever is purchased with it. Bitcoin can be used to purchase some goods and services, but as it is not yet widely accepted as a medium of exchange (MOU), the best way of establishing its purchasing power is to look at its exchange rate to a widely accepted MOU, such as the US dollar. This is BTCUSD over the last year:

That is an appreciating currency. Each unit of BTC now buys more USD than it did a year ago - rather a lot more, actually. Which means that each unit of BTC buys more goods and services than it did a year ago. Were the prices of goods and services quoted in bitcoins, we would see price falls, not rises. This is deflation, not inflation.

So if Bitcoin is deflating, not inflating, what on earth does Buterin mean when he says that Bitcoin is paying for security through inflation?

He does not mean economic (price) inflation. He means MONETARY inflation - sustained expansion in the supply of money. Bitcoin has a hard limit on the number of bitcoins that can ever be mined, but it is nowhere near that limit. At the present time, the supply of bitcoins is expanding at the rate of one every 10 minutes.

What Buterin means by "inflation" paying for security is that Bitcoin miners are rewarded for their validation of transactions by being given additional bitcoins, created "ex nihilo" as a result of their work ("proof of work") - which in practice means their expenditure of energy in validating transactions back through the chain. The longer the chain, the more energy it takes to validate transactions and the more difficult (and expensive) it becomes to mine additional bitcoins.

Now, we can argue about whether monetary inflation matters, and if so to what extent. In economic circles, the jury is out on this, but Bitcoin is ideologically driven by hard-money Austrian principles, so we might expect that its adherents are very concerned to limit the supply of money. But my objection here is to simple sloppiness in terminology. When people say "inflation", they generally mean price inflation. So if you mean monetary inflation, Vitalik, say so.

Ok, so we've cleared that up. Now on to my main objection to this piece.

Buterin is essentially discussing the relative merits of two different ways of paying miners for the validation of transactions: additional bitcoins, or transaction fees. There is a lot of geekery here, so I'm going to do my best to translate.

When Bitcoin reaches its hard limit on the supply of bitcoins, all future transaction validation will be rewarded with transaction fees, not additional bitcoins. Personally I am of the opinion that the switch to transaction fees might occur before then, since the cost of mining additional bitcoins will rise exponentially as the hard limit is approached, making it prohibitively expensive to mine them - this is a fine example of the law of "diminishing returns". But I could be wrong. Anyway, the point is that unless the Bitcoin community agree to raise the limit - which is the subject of fierce dispute at present - at some point Bitcoin will switch to a transaction-fees-only reward model.

Buterin's concern is that in a transaction-fees-only model, the fees need to be set high enough to discourage malicious operators from taking over the network by making miners offers they can't refuse. How much would it cost to take over the entire network? Buterin has some ideas:

Hence, we have $1.2-4m as an approximate estimate for a “Maginot line attack” against a fee-only network. Cheaper attacks (eg. “renting” hardware) may cost 10-100 times less. If the bitcoin ecosystem increases in size, then this value will of course increase, but then the size of transactions conducted over the network will also increase and so the incentive to attack will also increase. Is this level of security enough in order to secure the blockchain against attacks? It is hard to tell;it is my own opinion that the risk is very high that this is insufficient and so it is dangerous for a blockchain protocol to commit itself to this level of security with no way of increasing it.Translation: in a proof-of-work system, imposing a hard limit on the number of coins in existence is a VERY silly idea. (Bitcoin enthusiasts will no doubt disagree.)

Of course, Ethereum's proof-of-stake (investment) is MUCH better, natch:

In a proof of stake context, security is likely to be substantially higher. To see why, note that the ratio between the computed cost of taking over the bitcoin network, and the annual mining revenue ($932 million at current BTC price levels), is extremely low: the capital costs are only worth about two months of revenue. In a proof of stake context, the cost of deposits should be equal to the infinite future discounted sum of the returns; that is, assuming a risk-adjusted discount rate of, say, 5%, the capital costs are worth 20 years of revenue. Note that if ASIC miners consumed no electricity and lasted forever, the equilibrium in proof of work would be the same (with the exception that proof of work would still be more “wasteful” than proof of stake in an economic sense, and recovery from successful attacks would be harder); however, because electricity and especially hardware depreciation do make up the great bulk of the costs of ASIC mining, the large discrepancy exists. Hence, with proof of stake, we may see an attack cost of $20-100 million for a network the size of Bitcoin; hence it is more likely that the level of security will be enough, but still not certain.Well, OK, a perpetuity pricing model does make sense, though the 5% discount rate is huge for a system that supposedly disperses risk and is free from price inflation. But if the price of security in a transaction-fee system is that far below the price of security in a sensibly discounted return-on-investment model, the transaction fees aren't anywhere near high enough.

This is the uncomfortable truth that Buterin is trying to avoid. The security he thinks his system needs is expensive. Users might not be willing to pay for it.

In a transaction-fee-only system, fees that are high enough to discourage miners from selling out to a higher bidder may be too high to discourage users from transferring to another system. Losing your users is every bit as bad as losing your miners. So having discarded the hard cap on the coin supply, Buterin thinks he has a solution to the problem of expensive transaction fees (or poor security). He wants to identify the optimum mix of new coins and transaction fees in miners' rewards. And he tries to use Ramsey pricing to determine it.

Sadly, Buterin's example misconstrues the context of Ramsey pricing. The differential markup is not because of social harm to purchasers of the products: there is no captive audience. No, the differential markup is to protect the producers of the higher-value good, since the higher price elasticity of demand for their product means that the railway's markup would cause them greater loss of sales than the equivalent markup on a product with lower price elasticity of demand. It's the equivalent of a variable sales tax - indeed Ramsey pricing is sometimes used in tax policy.

Clearly, we do not have a similar situation here. What we have is a single good (coins) which are transported at a fixed fee (transaction fee). The problem is simply one of supply and demand. If the price demanded by miners for supplying security is too high, users will vote with their feet. If the amount that users are prepared to pay for security is too low, miners will sell out to attackers. There should be some equilibrium point at which most users will pay an amount that most miners are happy with: there will remain a tail risk of takeover, just as there will remain a tail risk that the crypto equivalent of Uber entices away the users by massively undercutting the transaction fees. Equilibrium is NOT a risk-free position.

Buterin thinks that it is not possible to set transaction fees high enough to reduce the risk of attack to acceptable levels. I might say that in a decentralised democratic system, if users don't want to pay for security, they shouldn't have to. If the consensus is that a raised risk of attack is an acceptable price to pay for lower transaction fees, that is how it should be. Buterin has no right to start dictating to people what level of attack risk they should be allowed to take.

And he is quite wrong to suggest that mining rewards (new coins) can be used to subsidise transaction fees. Coin rewards for miners are in fact an additional cost for the users. This brings me back to where I started in this article. He misused the term, but he was right about inflation - though he didn't follow it through.

Classically, expanding the money supply is associated with price inflation. In a whole economy, the relationship is very complex. But in this case, it is much less so. BTCUSD has been rising constantly over the last year, which shows us that the rate of expansion is less than the rate of increase in demand for the coins. Nonetheless, the price would have risen more if no new coins were produced. Even though Bitcoin is deflating, the difference between the price (in USD) of 1 BTC when the money supply is expanding and the price (in USD) of 1 BTC when the money supply is fixed is a real cost to the users of the system, since it means their bitcoins don't buy so much. It is equivalent to a higher transaction fee.

So Ramsey pricing just doesn't apply. What we are really dealing with here is human preferences. Do miners prefer to receive transaction fees or new coins? Do users of the system suffer from money illusion - so prefer to have lower transaction fees and a higher rate of price inflation (or lower rate of deflation)? It should be possible to determine some mix of coin rewards and transaction fees that keeps most people happy. And it is entirely conceivable that Bitcoin might choose to operate with transparently higher transaction fees as the price of retaining its hard cap, while Ethereum chooses to run with lower fees and some price inflation. That is for the respective communities to decide.

In fact, what Buterin is trying to solve here is exactly the same conundrum as central banks face (and have never solved). What is the optimum balance of interest rates and inflation? Should we fix interest rates (transaction fee) at some level, and allow inflation (coin supply) to flex? Or should we fix inflation (coin supply) and allow interest rates (transaction fee) to flex? Or some combination of flexible coin supply AND transaction fee?

Whatever approach is adopted, in a simple niche system like Bitcoin or Ethereum the equilibrium would be pretty much the same. The system would have to be far more complex for the choice of target to make much difference. The mix of coin rewards and transaction fees is largely irrelevant: it is the total cost of security that matters, not how it is paid for. In his concern to protect his system from attack, Buterin is chasing a chimera.