Summary:

Eurozone growth figures came out today. And they are horribly disappointing. Everyone undershot, apart from Spain which turned in a remarkable 1% quarter's growth, and Greece which somehow managed an even more incredible 0.8% (yes, I will write about this, but not in this post). France didn't grow at all, Italy all but stagnated at 0.2%, and even the mighty Germany only managed 0.4%. Despite low oil prices, falling commodity prices, weak Euro and the ECB's QE programme, Eurozone quarterly growth is a miserable 0.3%. Maybe it's just me, but I can't help thinking that something just isn't working in the Eurozone.Among the most disappointing performances was Finland's. Back in May, the European Commission confidently predicted that growth would return in 2015:But what is actually happening is this (this chart includes today's figures):Finland has been in recession for most of the last three years. True, towards the end of 2014 it did look as if it was beginning to recover. But that was a damp squib. Today's figures show that the economy contracted by 1% in the second quarter of 2015. So what on earth went wrong? It doesn't appear to have been the financial crisis. Finland did get clobbered, yes - it suffered a deep recession in 2009, as the chart shows - but it bounced back quickly and in 2010-11 was growing at a highly respectable 5%. Then it collapsed.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: austerity, deficit, Financial Crisis, finland, fiscal policy, GDP, sovereign debt, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Eurozone growth figures came out today. And they are horribly disappointing. Everyone undershot, apart from Spain which turned in a remarkable 1% quarter's growth, and Greece which somehow managed an even more incredible 0.8% (yes, I will write about this, but not in this post). France didn't grow at all, Italy all but stagnated at 0.2%, and even the mighty Germany only managed 0.4%. Despite low oil prices, falling commodity prices, weak Euro and the ECB's QE programme, Eurozone quarterly growth is a miserable 0.3%. Maybe it's just me, but I can't help thinking that something just isn't working in the Eurozone.Eurozone growth figures came out today. And they are horribly disappointing. Everyone undershot, apart from Spain which turned in a remarkable 1% quarter's growth, and Greece which somehow managed an even more incredible 0.8% (yes, I will write about this, but not in this post). France didn't grow at all, Italy all but stagnated at 0.2%, and even the mighty Germany only managed 0.4%. Despite low oil prices, falling commodity prices, weak Euro and the ECB's QE programme, Eurozone quarterly growth is a miserable 0.3%. Maybe it's just me, but I can't help thinking that something just isn't working in the Eurozone.Among the most disappointing performances was Finland's. Back in May, the European Commission confidently predicted that growth would return in 2015:But what is actually happening is this (this chart includes today's figures):Finland has been in recession for most of the last three years. True, towards the end of 2014 it did look as if it was beginning to recover. But that was a damp squib. Today's figures show that the economy contracted by 1% in the second quarter of 2015. So what on earth went wrong? It doesn't appear to have been the financial crisis. Finland did get clobbered, yes - it suffered a deep recession in 2009, as the chart shows - but it bounced back quickly and in 2010-11 was growing at a highly respectable 5%. Then it collapsed.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: austerity, deficit, Financial Crisis, finland, fiscal policy, GDP, sovereign debt, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Angry Bear writes GDP Grows 2.3 Percent

Merijn T. Knibbe writes ´Extra Unordinarily Persistent Large Otput Gaps´ (EU-PLOGs)

Angry Bear writes A Fiscal Policy in a Global Context?

NewDealdemocrat writes Real GDP for Q3 nicely positive, but long leading components mediocre to negative for the second quarter in a row

Among the most disappointing performances was Finland's. Back in May, the European Commission confidently predicted that growth would return in 2015:

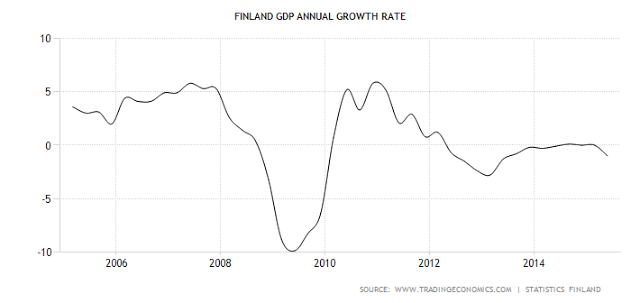

But what is actually happening is this (this chart includes today's figures):

Finland has been in recession for most of the last three years. True, towards the end of 2014 it did look as if it was beginning to recover. But that was a damp squib. Today's figures show that the economy contracted by 1% in the second quarter of 2015.

So what on earth went wrong? It doesn't appear to have been the financial crisis. Finland did get clobbered, yes - it suffered a deep recession in 2009, as the chart shows - but it bounced back quickly and in 2010-11 was growing at a highly respectable 5%. Then it collapsed. It would be easy to blame that on the Greeks, wouldn't it? Or maybe the oil price rises at that time?

No. This is not a story of Eurozone macroeconomic imbalances and oil price shocks. Rather, it is the sad tale of a country that allowed itself to become dependent not just on one industry, but on one company.

Some years ago, I went for an interview at Pfizer's plant in Sandwich, Kent. As I drove through the town, I was struck by how dependent the local economy had become on Pfizer, its only significant employer. I found myself wondering what would happen if it ever left. And in February 2011, it did. Three thousand people lost their jobs when Pfizer left. But more importantly, the entire local economy collapsed. Everything from hotels to bookshops, from the summer festival to Christmas parties, was clobbered by Pfizer's decision. Four years later, Sandwich still has not recovered. When the heart has been ripped out of an economy, recovery takes a long time.

And when this happens to an entire country, the consequences are disastrous. From the EC's country report, here is Nokia's contribution to Finnish GDP:

And here is Nokia's share of Finnish exports:

The crowding-out of other export industries by Nokia's dominance is painfully evident.

The appalling effect of Nokia's dominance on the Finnish economy is spelled out by the European Commission (their emphasis) and illustrated in the charts below - though it wasn't the only Finnish export industry to shrink in the aftermath of the financial crisis:

Similarly to its decisive role in the boom period, the collapse of Finnish mobile handset exports accounts, in itself, for around half of the total decrease in the Finnish export market share of goods. The share of mobile handsets in the Finnish goods export declined from 13 % in 2000 to 1 % in 2013. This also reduced the share of high-tech products in Finnish exports from around 20 % at the beginning of the 2000s to around 5 % in 2013. Filtering out the impact of the trade in mobile handsets, the accumulated market share decline would have been close to 20 % between 2008 and 2013, i.e. still the largest in the EU-28. It illustrates that the loss in export market shares also concerned other goods and reflected an adverse change in the international demand structure from a Finnish point of view.

In short, Finland is Sandwich, on a simply gigantic scale. No wonder it has struggled to recover.

But wait. Nokia's collapse occurred at the time of the financial crisis. Yet Finland did recover, albeit briefly. At the time of the deepest trade deficit, Finland's GDP was growing at 5% per annum. Why was this?

In a word, imports. The European Commission explains (their emphasis):

The second main driver of the deteriorating current account and trade balance is the growth in imports for domestic demand purposes, although this factor is often overlooked. Import growth was boosted by the increasing consumption of households, in particular after 2008 (Graph 2.2.17) and by the growing import intensity of domestic demand from 23 % in 2000 to 26 % in 2011. Between 2000 and 2008, the increasing consumption ratio has reflected growing real consumption. Although real consumption of households declined in 2009, it quickly recovered in 2010 and 2011 and broadly stabilised afterwards. This, in parallel with a GDP that is still below its pre-crisis level, resulted in an increasing import ratio.Imports rose sharply as exports collapsed, because household consumption continued to increase: (note that on the RH chart net exports are shown inverted, i.e. rising line indicates falling net exports):

But how did households maintain their consumption? Here's how (my emphasis):

After 2009, consumption was supported by improving real gross disposable income, which increased until 2011 and stabilised afterwards in light of the slow labour market adjustment (in both wages and employment) to deteriorating growth developments and due to enhanced current transfers to households. In short, despite the decline in national income, households could maintain their real consumption without decreasing their saving ratio.Keynesian countercyclical fiscal stimulus, in other words. This is what it did to the government budget deficit:

In 2009-10, Finland's budget balance switched abruptly from a surplus of nearly 6% of GDP to a deficit of nearly 4% of GDP. That accounts for nearly all of the 10% fall in GDP that Finland suffered in 2009.

Putting this together, we can see that Finland's recovery from the financial crisis was driven almost entirely by a large rise in government spending to support households. Interestingly, tax revenues don't seem to have fallen relative to GDP - the budget deficit seems to have been entirely caused by spending increases.

And we also now know why Finland's GDP collapsed from 2011. The government reduced its budget deficit, forcing households to cut back spending. Only when the budget deficit started to rise again in 2012 did GDP start to improve.

So where are we now? Finland's budget deficit is currently 3.2% of GDP - twenty basis points above the Maastricht limit - and is expected to rise further. And Finland's debt/GDP, which is currently just above the Maastricht limit of 60% of GDP, will also rise, not only because of its fiscal deficit but also because of falling GDP.

This chart shows that a high proportion of the fiscal deficit is considered structural. Admittedly, this forecast assumes return to growth in 2015. But what this shows is the supply-side damage done by the loss of Nokia. Considerable structural redevelopment will be needed to repair it.

Sadly, the European Commission gives little weight to this. It makes some sensible recommendations about product market reforms, and rightly highlights the importance of entrepreneurship and innovation. But there are no significant recommendations for measures to support innovative start-ups and SMEs, and there is no discussion whatsoever of Finland's need to attract FDI.

Instead, there is an unhealthy focus on fiscal finances that totally fails to acknowledge the need for continuing fiscal support, probably for a long period of time. In the European Semester review recommendations in May 2015, top priority is given to reducing the deficit:

Ensure that the excessive deficit is brought below 3% of GDP in a timely and durable manner by [XX] in line with Finland's obligations under Article 126 TFEU. Continue efforts to reduce the fiscal sustainability gap and strengthen conditions for growth.

Fiscal tightening now is clearly inappropriate. The economy is not strong enough to cope with it. Even had it returned to growth as the European Commission predicted, unemployment in Finland is nearly 10% and youth unemployment is double that. There is little investment activity by corporations and not much in the way of FDI. Exports are stagnant and the current account is negative in relation to GDP: the recent improvement in the balance of payments is entirely due to improving terms of trade, probably due to falling oil prices. Tightening now, when there has not been sufficient supply-side development to plug the gap left by Nokia, will drive the economy deeper into recession and set back the development of new industries, which Finland desperately needs.

But even with fiscal support, it will take Finland a long time to recover from the damage done to its productive capacity not just by the loss of Nokia, but by the over-dependence on Nokia in previous years.

And the moral of the story is this. If you are a small country, never, ever allow yourself to become the home of a large multinational.

Related reading: