In the past few days, I have read three pieces from Economists for Brexit - now renamed "Economists for Free Trade" - extolling the virtues of "hard" (or "clean") Brexit and calling for the UK to drop all external tariffs to zero unilaterally after Brexit. Two are written by professors of finance (Kent Matthews and Kevin Dowd). The third is from the veteran economist Patrick Minford.All three of these pieces wax lyrical about the benefits to GDP and welfare from unilaterally reducing external tariffs to zero. But bizarrely, not one gives adequate consideration to the currency effects of trade adjustment and the likely monetary policy response. Minford's brief discussion contains a schoolboy error (of which more shortly). The other two never mention it at all.In today's free-floating

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Brexit, currency, Economics, GDP, inflation, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

In the past few days, I have read three pieces from Economists for Brexit - now renamed "Economists for Free Trade" - extolling the virtues of "hard" (or "clean") Brexit and calling for the UK to drop all external tariffs to zero unilaterally after Brexit. Two are written by professors of finance (Kent Matthews and Kevin Dowd). The third is from the veteran economist Patrick Minford.

All three of these pieces wax lyrical about the benefits to GDP and welfare from unilaterally reducing external tariffs to zero. But bizarrely, not one gives adequate consideration to the currency effects of trade adjustment and the likely monetary policy response. Minford's brief discussion contains a schoolboy error (of which more shortly). The other two never mention it at all.

In today's free-floating currency regime, trade shifts and currency movements are intimately linked. Indeed, for some countries, trade shifts are driven more by capital flows and associated currency valuation changes than they are by trade policy. So I am at a loss to understand how anyone can seriously discuss trade policy without considering currency effects and monetary policy. Especially professors of finance, who really should know better.

First, let's consider how trade policy changes affect currency exchange rates. Recently, there was much discussion of a "border adjustment tax" by policymakers in the USA. The idea was that imposing a tax of, say, 20% on all imports to the USA would discourage businesses and consumers from buying imports, thus encouraging domestic US businesses at the expense of foreign exporters to the US. Additionally, US exporters would be exempt from import taxes, thus encouraging exports. The combination of the tax on imports with exemption from the tax for exporters is the reason why this is called a "border adjustment tax". It is similar to a VAT, except that VAT is typically also imposed on domestic production.

American economists Caroline Freund and Joseph E. Gagnon studied the effects of border adjustment taxes in a number of countries. They concluded that changes in the inflation-adjusted trade weighted exchange rate ("real effective exchange rate", or RER) wipe out any advantage from a border adjustment tax:

Overall, our results support the basic theoretical conclusion that RER movements fully offset borderadjusted consumption taxes, including the VAT. Our results also suggest that a large share of the movement in the RER comes via consumer prices. In particular, increases in VAT rates temporarily increase inflation, which permanently changes the RER. There is little evidence of any significant effect of border-adjusted consumption taxes on the current account balance, although there may be different effects on the components of the current account. Most of the adjustment occurs within three years.For foreign exporters who are paid in their own currency, the effect of the import tax is a wash: the tax raises the sales price of their products in the importing country, but the strengthening dollar entirely offsets this. In theory, importers could force FX losses on to foreign exporters by insisting on paying in their own currency: but exporters faced with FX losses are likely to respond either by raising export prices in their own currency or by diverting sales elsewhere. After all, there are always other markets.

For US exporters, the effect is also a wash, since any benefit they get from being excused the import tax is lost in the exchange rate appreciation. No-one benefits from a border adjustment tax.

But wait. Aren't Economists for Free Trade talking about tariffs, not taxes?

As Gavyn Davies explains, the US's border adjustment tax plan is equivalent to a tariff on imports and a subsidy on exports. Unilaterally reducing all tariffs to zero is therefore equivalent to reducing taxes on imports without adding an export subsidy.

For example, if the average import tax is currently 25%, made up of 20% VAT and 5% external tariff, reducing the external tariff to zero is a 20% cut in import taxes. Note that domestic businesses do not benefit from this cut, and neither do exporters. Trading conditions therefore become more difficult for domestic businesses relative to foreign exporters, while export trading conditions remain unchanged if other countries do not respond to the tariff cut.

Economists for Free Trade argue that falling nominal import prices would improve people's real disposable incomes, giving a demand boost to the economy which should kickstart a supply-side response. Additionally, nominal business input costs would fall, enabling a production increase to meet higher consumer demand and improve export performance, while increased competition from imports would force domestic businesses to raise productivity, improving both GDP and nominal wage growth. It sounds like a paradise. What's not to like?

Sadly, this omits the effect of exchange rate changes. If raising taxes on imports causes the currency exchange rate to rise sufficiently to wipe out the benefit to domestic businesses, similarly we would expect cutting import taxes to cause real exchange rate depreciation sufficient to wipe out the benefit to foreign exporters.

There would, however, potentially be a benefit to exporters from the exchange rate depreciation. Therefore, we might expect that unilaterally reducing import tariffs to zero would give a boost not to domestic demand but to exports. This would apply even if trade partners did not reciprocate with tariff cuts of their own.

Neither Kent Matthews nor Kevin Dowd mention this. Worse, Minford bizarrely assumes that sterling depreciation only applies to exporters, not importers:

Now, think about what happens if we reduce our trade barriers on imports. We reduce the prices of imports to consumers, and this creates both a gain to them and more competition with our home producers, forcing them to raise productivity. This is a most definite and permanent gain to our economy - a rise in consumer welfare and in GDP. A natural by-product of this is, as we produce more, we export more to pay for our higher imports. In the short run, this comes about by a fall in sterling to stimulate these sales; in the long run, once our new markets are established, sterling recovers to its old level, its job done. We are quite familiar in the UK with this sterling movement; the pound regularly falls when we need to stimulate output in export industries, as it has done after Black Wednesday when we left the ERM, also after the financial crisis, and latterly after Brexit.The exchange rate depreciation arising from unilaterally cutting import tariffs would benefit exporters while making no difference at all to importers? Really?

This is the schoolboy error I mentioned at the start of the post. It is by no means the only glaring error in Minford's paper, but it is the one that concerns me here. Combined with persistent confusion of nominal and real effects throughout the paper, it fatally undermines his entire economic analysis.

Falling import prices would indeed encourage consumers to spend more initially. But as the effects of the sterling depreciation began to bite, import prices would rise again. The consumer stimulus would fizzle out and sales would return to where they were before. Freund and Gagnon's research is definitive. The deflationary stimulus would be temporary, not permanent, and would be followed by rising inflation that wiped out its short-term benefits.

On the export side, as I've already noted, sterling depreciation should boost exports - although as the UK is very integrated in international supply chains, the effect is highly uncertain and could be very short term. But there is no evidence to support Minford's assertion that in the long run sterling's exchange rate would recover. To the contrary, Freund and Gagnon show that the RER adjustment is permanent - and it is the real, not the nominal, exchange rate that matters for export competitiveness.

Nor would the nominal exchange rate necessarily recover, either - at least not permanently. In each of the examples that Minford gives, the pound did indeed bounce back to some extent as the economy recovered: but over the much longer term, the story is one of continual decline. For example, sterling's exchange rate versus the dollar has declined from $4.70 in 1915 to $1.28 today.

This is not to say that cutting import tariffs is a bad thing. Reducing tariffs to zero as part of a free trade agreement usually benefits everyone. But unilaterally cutting tariffs simply cannot give the real benefits that Economists for Brexit claim. The nominal changes might look good, but they would be entirely illusory.

However, Dowd cites Hong Kong and Singapore as examples of countries that successfully operate zero-tariff regimes. If those countries can do it, why can't the UK?

There is an obvious size difference, of course. There are also significant differences of culture and regime: Singapore, for example, has high levels of state ownership and practises severe financial repression. But this post is about currency effects. Why doesn't the benefit of their zero-tariff regimes disappear in currency adjustments?

The simple answer is that neither country has a freely floating exchange rate. Hong Kong has a currency board which pegs its currency to the US dollar. Singapore's monetary authority explicitly maintains the value of the Singapore dollar within an (undisclosed) band. Neither country would allow its currency to depreciate sharply as a freely floating British pound would be likely to under a zero-tariff regime.

A unilateral zero-tariff regime could deliver the domestic benefits that Economists for Free Trade envisage if the Bank of England actively intervened to prop up sterling. This appears counterintuitive, but remember that the benefits are supposed to accrue from falling real import prices. Nominal falls accompanied by sterling depreciation would not deliver those benefits. Therefore, sterling would have to be prevented from depreciating. This would mean sharp rises in interest rates even while consumer prices were undergoing a short-term fall. In the UK's highly indebted, fragile economy, the consequences for financial stability could be severe. Anyway, why would you want to hobble exports to encourage a consumer boom, in a country that has large trade and fiscal deficits and relies on debt-financed consumer spending to maintain economic growth?

Not one of the Economists for Free Trade mentions any of this, let alone discusses it. The total absence of any consideration of currency effects in both Dowd's piece and Matthew's suggests to me that they don't understand the connection between trade and currency, which as they are not trade economists is perhaps not all that surprising. But if their grasp of trade economics is really so weak, why are they writing about it at all?

And as for Minford - words fail me. This man is a professor of economics, but his paper is riddled with elementary errors. Are these people really the best and brightest economic brains in the Brexit camp? I sincerely hope they are not. For if they are, God help us.

Related reading:

Brexit, trade and echoes of the past

Some unpleasant trade realities

The dominance of Brexit

Three reasons why the UK could be going into recession - Forbes

The "Britain Alone" scenario: how Economists for Brexit defy the laws of gravity - LSE

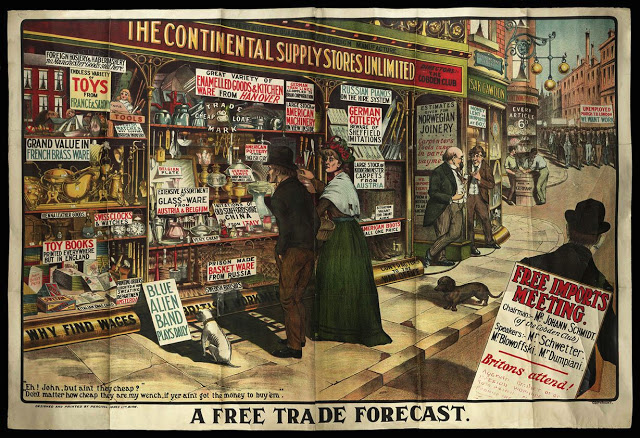

Brexit free trade illusions from the 19th century - FT

The economic benefits of Brexit, revisited and rectified - Professor Alan Winters

Image from Real-World Economics Review Blog.