"No deal for Britain is better than a bad deal", says Theresa May. Her Brexit sidekick David Davis appeals to MPs not to "tie her hands". And that master of flannel, trade secretary Liam Fox, says that leaving without a deal would be "not just bad for the UK, it's bad for Europe as a whole".These three statements sum up the hopes of the Brexiteers. The idea seems to be that if the UK adopts a really strong stance in its forthcoming negotiations with the EU, the Europeans will be so horrified at the prospect of the UK leaving without any agreement that they will cave in and give the UK what it wants. Welcome to the Brexit game of chicken.On the face of it, the UK government's negotiating principles appear sound: set out your red lines, make it clear that you won't tamely agree to everything the other side wants and that you will walk away rather than give ground on things that really matter. But if you are going to play brinkmanship, you really have to understand your opponent. The EU is well versed in this game - and it knows how to win.So, how credible is May's threat to walk away from negotiations? Davis's intervention is clearly intended to make it credible. If Parliament can overturn her decision and send her back to the negotiating table, then her position is much weaker. On this occasion, therefore, perhaps they are right.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Brexit, EU, Greece, Grexit, trade, UK, WTO

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

Merijn T. Knibbe writes ´Extra Unordinarily Persistent Large Otput Gaps´ (EU-PLOGs)

Merijn T. Knibbe writes In Greece, gross fixed investment still is at a pre-industrial level.

Robert Skidelsky writes Speech in the House of Lords Conduct Committee: Code of Conduct Review – 8th of October

"No deal for Britain is better than a bad deal", says Theresa May. Her Brexit sidekick David Davis appeals to MPs not to "tie her hands". And that master of flannel, trade secretary Liam Fox, says that leaving without a deal would be "not just bad for the UK, it's bad for Europe as a whole".

These three statements sum up the hopes of the Brexiteers. The idea seems to be that if the UK adopts a really strong stance in its forthcoming negotiations with the EU, the Europeans will be so horrified at the prospect of the UK leaving without any agreement that they will cave in and give the UK what it wants. Welcome to the Brexit game of chicken.

On the face of it, the UK government's negotiating principles appear sound: set out your red lines, make it clear that you won't tamely agree to everything the other side wants and that you will walk away rather than give ground on things that really matter. But if you are going to play brinkmanship, you really have to understand your opponent. The EU is well versed in this game - and it knows how to win.

So, how credible is May's threat to walk away from negotiations? Davis's intervention is clearly intended to make it credible. If Parliament can overturn her decision and send her back to the negotiating table, then her position is much weaker. On this occasion, therefore, perhaps they are right. Parliament cannot be allowed to veto a "no deal" exit. To do so would indeed tie Theresa May's hands. She must have the freedom to end negotiations without a deal.

But Parliament is the least of her problems. Theresa May's real difficulty is that she is dealing with a hardened opponent that is not afraid to take pain in order to get what it wants. And to make matters worse, she has a hard deadline. The UK will leave the EU two years after Article 50 is triggered. The deadline can be extended, but it would require agreement from all 27 EU countries. There is no guarantee that in the event of no deal, they would agree to extend the deadline. In fact, there would be a strong incentive for them not to do so. If negotiations ran to the wire, the EU would need to concede virtually nothing. All it would need to do is put its terms on the table and say "take it or leave it".

And if you think the EU would not do this, you have learned nothing from the last few years. In 2015, Greece thought it could negotiate a new deal with the EU. So it set out its red lines, made it clear it would not accept the EU's terms, and threatened to walk away from negotiations - and indeed, from the Euro - if it didn't get what it wanted. For a while, it looked as if it might follow through on its threat: the resounding "NO" to the EU's terms in the Greek referendum should have led to exit from the Euro. But when the European Council explicitly faced Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras with a choice between accepting their terms or leaving the Euro, he balked. And at that moment, he lost the game. The Greek government's threat to jump over the cliff was exposed as a bluff.

From that moment on, the end was inevitable. In a bruising overnight negotiation, Tsipras conceded almost everything that his government had previously rejected. And since then, further concessions have been made. The "red lines" have been repeatedly crossed. The Greek government is tamely accepting everything the EU demands - because the only alternative is jumping over the cliff edge that they stepped back from in July 2015.

The lesson is clear. If you are going to play the cliff edge game, you must be prepared for the possibility that the other side will push you over. Especially if your opponent is the EU.

Of course, the UK has already decided to jump over the cliff. Indeed, that is what the negotiation is about. It wants to negotiate a soft landing. Clearly, therefore, a European Council "accept our terms or leave" confrontation is not going to happen in this case. But that doesn't mean that the UK has a strong position. It doesn't.

To understand this, we have to consider the nature of the beast. In theory, the negotiations could be limited to the terms of the "divorce" - the status of EU nationals in the UK and UK nationals in the EU, the division of assets, the dismantling of common agreements, the final bill for ongoing responsibilities such as pensions. Leaving the EU without agreement on these would be horrible for everyone.

The UK's attempts to use security, intelligence and the status of EU nationals in the UK as bargaining chips have already been criticised. In all of these, it is hard to see that the "cliff edge" game is remotely credible: unilaterally ending cooperation over security, policing and intelligence would be utter folly, while the humanitarian cost of deporting EU nationals would be appalling. I think it is unlikely that the EU will play brinkmanship over security and intelligence: the EU has as much to lose as the UK, so agreement seems likely early in the negotiation. And the easy way of defusing the "hostages" problem is for the EU to offer UK nationals right-to-remain unilaterally, and then dare the UK to deport EU nationals. The UK government is already facing strong criticism at home for its attitude to EU nationals: international opprobrium as well might be a bridge too far. Nor is the EU likely to go into an exit with no agreement about the 60bn Euros it says it wants from the UK. Once the UK was no longer a member of the EU or under the jurisdiction of the ECJ, the EU would have no power to force it to pay up. No, there will be a deal on all these matters.

But trade is an entirely different matter. The EU and the UK appear to be poles apart. The EU negotiators seem to be intent on keeping the negotiations narrowly focused on the terms of the "divorce" and kicking trade discussions into the long grass. In contrast, the UK government has said it intends to forge a "new customs arrangement" with the EU, though it has not as yet defined what it means by that. And it lays claim to tariff-free trade:

We do not seek to adopt a model already enjoyed by other countries. The UK already has zero tariffs on goods and a common regulatory framework with the EU Single Market. This position is unprecedented in previous trade negotiations. Unlike other trade negotiations, this is not about bringing two divergent systems together. It is about finding the best way for the benefit of the common systems and frameworks, that currently enable UK and EU businesses to trade with and operate in each others’ markets, to continue when we leave the EU through a new comprehensive, bold and ambitious free trade agreement.Eh, what? The UK government thinks the UK can have the benefits of Single Market membership without actually being a member of it? This is not remotely credible. Zero tariffs on trade and a common regulatory framework are not a side effect of the Single Market, they are its very nature. It would not be in the EU's interests for a non-EU member to have the same benefits as EU members. When the UK leaves the Single Market, therefore, there will no longer be zero tariffs and a common regulatory framework. The costs of doing business with the EU will go up.

How much they will go up depends on what deal the UK government manages to do with the EU. I confess I am not hopeful. The EU drives a very hard bargain. So, what happens if May ends up saying "no deal"?

Leaving the EU with no trade deal would mean that the UK would immediately revert to "most favoured nation" (MFN) status under the World Trade Organisation's rules as far as the EU was concerned. Much nonsense is talked about this, mostly by people who don't know what they are talking about. The "Clean Brexit" economists at the Policy Exchange, for example, blithely say this:

“WTO rules” is often presented as “deeply damaging” and “the hardest of hard Brexits”. We disagree. Tariffs under WTO rules are relatively low and falling. We already conduct around half of all our trade under WTO rules - beyond the Single Market or other formal free trade agreements (FTAs) - with the rest of the world. Both the US and China trade heavily with the EU, under WTO rules and we can do the same. Already, our WTO-rules trade is not only the biggest part - it is also fast-growing and records a surplus.Aarrggh. There is a world of difference between trading with countries under existing trade tariffs which have been reducing in recent years, and introducing new trade tariffs where currently there are none.

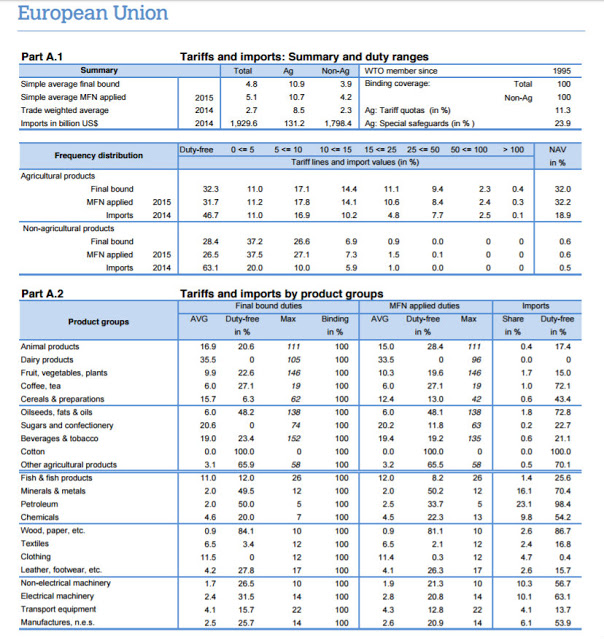

The potential impact on the UK's trade with the EU from introducing new tariffs is considerable. I've reproduced here the WTO's table showing the current EU MFN tariffs:

Remember that the UK currently faces no tariffs on trade with EU countries. Chemicals are one of the UK's principal exports to the EU: after a "no-deal" Brexit, their export price would rise by 4.5%. This might be offset by a further fall in the value of sterling, but that creates problems on the import side. Few manufacturers are immune from import price rises, these days.

These are, of course, goods tariffs. The picture for services is much less clear. The WTO framework for services is at best a work in progress: flawed though it is, the EU's single market in services is far more developed. The "common regulatory framework" mentioned by the UK government is one of the principal benefits of the single market in services. Immediately on exit, this would be unlikely to change much, though the UK government's plans to impose restrictions on the free movement of people will negatively impact services trade right from the start. But over time, as EU and UK law and regulation diverged, services trade would become more and more difficult. The UK is also a major exporter of services to the rest of the world: the US is its largest trade partner in services. Much of this is because it is used as a gateway to the EU by service industries, particularly financial services. Once the UK can no longer perform that function, those service industries might disappear for good. So reverting to WTO rules could cause not only services trade with the EU to decline, but also services trade with the rest of the world.

The EU's MFN tariffs are also currently applied by the UK on its trade with non-EU countries with which the EU has no separate free trade agreement. The UK enjoys WTO membership by virtue of its EU membership, so as part of the Brexit process it will have to negotiate separate membership of the WTO, including setting up its own tariff schedules. Although there are calls for the UK to unilaterally abandon import tariffs, it seems much more likely that the EU's current WTO tariff schedule will form the basis for the UK's own tariff schedule post-Brexit.

After a no-deal Brexit, the UK would have to impose on imports from the EU the same MFN tariffs as it imposes on imports from non-EU countries. If the UK's new WTO schedules were based on the existing EU ones, then the impact on some agricultural imports, in particular, could be rather high, according to a study produced for the National Farmers' Union in April 2016:

.....a tariff of 30-40% would be applied on wine and cheese - two items for which the UK runs a significant deficit with the EU (net-imports of about 2,200 million and 1,250 million euro respectively, see Figure 3.1). In addition, imports of several meat product items would become subject to tariffs that could exceed 30% and might be even close to 70% or 90%, depending on the type of meat. All in all, the UK consumer will face higher prices for many items that are imported, which will only alter, if the UK government negotiates preferential access with the EU when leaving the Union.Goodbye to cheap Prosecco, then. And that's without considering the impact of the UK's exclusion from the EU's "tariff-reduced quotas" - see the top RH corner of the table above for the likely excluded rate on agricultural products

.

None of this is good news for the UK. They are not great for the EU either, but EU countries could be forgiven for thinking that the loss of one country from the trading bloc would not make a great deal of difference - after all, there are still 27 of them and they can all trade freely with each other, as well as with the rest of the world under existing tariff arrangements. The UK, however, would be facing new tariffs on at least 45% of its exports, and it also would be obliged to impose MFN tariffs on over 50% of its imports.

The truth is that May's threat to leave the EU on WTO rules is no more credible than Alexis Tsipras's threat to leave the Euro. Leading the UK over the cliff edge onto a pile of jagged rocks is not delivering the best outcome for the UK. She would pay the price for that folly at the ballot box in 2020, or earlier if she lost the support of her (already restive) back-bench MPs. She has no choice but to try to negotiate some kind of soft landing. So the attempt to stifle Parliament is, once again, wrong. She must be chained to the negotiating table, even if it takes a Parliamentary veto to do it.

But the EU can walk away. After all, if it does nothing, the UK leaves on WTO rules that are a lot more damaging for the UK than they are for the EU. So the EU holds the upper hand. And the EU likes to play brinkmanship, especially when invited to do so by a foolhardy government. So my guess is that there will be a transitional deal. It will be hashed out in a brutal all-nighter just before the Article 50 notice expires. And in that meeting, May will agree to every single one of the EU's terms - because although they will fall a long way short of the benefits the UK currently enjoys, they will be better than the alternative.

The game will play out for the UK just as it did for Greece and Cyprus. And if any other governments are thinking of playing chicken with the EU - be warned. You will end up as roadkill.

Related reading:

Greece: The Game Is On Again - Forbes

Greece, the EU and the IMF are dancing with death - Forbes

Tsipras in the crucible

Sowing the wind

UK Perspectives 2016: Trade with the EU and beyond - ONS

Image by Gerald Scarfe.