The failure of Carillion has brought to light widespread moral hazard in the outsourcing sector. For years, companies that deliver crucial public services relied on expectation of government support to keep their borrowing costs low and enable them to please shareholders by giving dividends they couldn't afford. They, and the banks and investors that funded them, assumed they were too important to fail. So when Carillion was on the brink of failure, RBS tightened the screws, clearly believing that the UK government would eventually cough up (my emphasis): RBS....insisted that this revised arrangement "would be in place until support from [the Government] had been agreed and that the terms of this support would determine whether other uncommitted facilities with RBS would be

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Capital, cash, loss, profit

This could be interesting, too:

Frances Coppola writes Silvergate Bank – a post mortem

Peter Dorman writes Extending Capital to Nature, Reducing Nature to Capital

Frances Coppola writes Tether’s smoke and mirrors

Frances Coppola writes A Financial View of Labour Markets

The failure of Carillion has brought to light widespread moral hazard in the outsourcing sector. For years, companies that deliver crucial public services relied on expectation of government support to keep their borrowing costs low and enable them to please shareholders by giving dividends they couldn't afford. They, and the banks and investors that funded them, assumed they were too important to fail. So when Carillion was on the brink of failure, RBS tightened the screws, clearly believing that the UK government would eventually cough up (my emphasis):

RBS....insisted that this revised arrangement "would be in place until support from [the Government] had been agreed and that the terms of this support would determine whether other uncommitted facilities with RBS would be withdrawn".But they were wrong. The UK government refused to provide support, preferring to allow Carillion to fail. That decision shocked the outsourcing sector to the core. In effect, it had been summarily stripped of its implicit government guarantee. The gravy train has hit the buffers. Now, the outsourcing sector faces a very uncertain future.

Capita was the first to react. Its profits warning followed suspiciously hard on the heels of Carillion's collapse. Looking at its financials, it was quickly evident that the company was warding off a similar fate. Indeed, its CEO pretty much said so in his brutal assessment of the company's situation.

But Capita is far from the only company that will be forced into major restructuring. The entire outsourcing sector now looks extremely vulnerable. So I did a bit of forensic examination to see which companies would be the most sensitive to the loss of the implied government guarantee. G4S, Interserve, SERCO are all high on my list of companies that will have to deleverage significantly or face much higher borrowing costs. But one company above all stands out. Mitie.

Mitie is not exactly a household name. But its services portfolio affects everyone. It's a major contractor for central government, including the Scottish government and the Welsh Assembly, as well as local authorities, housing associations and educational bodies. It also runs services for many private sector organisations. The list of services it provides includes cleaning, catering, environmental services, custody (people, not finance), healthcare, security, document management, engineering, energy, housing & property management, consultancy & project management. In short, it has fingers in so many pies that it has lost sight of its core competency. When Capita announced its rights issue, analysts at the Royal Bank of Canada commented "we are not sure what Capita’s core business is any more". I would say the same of Mitie.

The lack of focus is all too clear from the 2017 interim results presentation . Here's Mitie's pictorial depiction of its business strategy:

I saw strategies like this when I was doing my MBA back in the early 1990s. I couldn't take them seriously then, and I can't now. This diagram is business school waffle. It could be transplanted into just about any company's strategy without alteration. Nowhere does it indicate what Mitie distinctively offers.

But the one thing it does suggest is that Mitie is desperate for contracts. "Move Mitie up the value chain" is code for "squeeze more work out of existing customers". Whenever I see that, alarm bells ring in my mind. When I was at Midland Bank, the strategy was to cross sell higher value-added services to our basic current account holders. Never mind if the bank had the skills and expertise to deliver those services, just sell them to the sheep. At that time, Midland was terribly short of money and desperately needed to sell higher value-added services. Eventually, of course, it was taken over by HSBC. But the mis-selling of insurance, endowment mortgages and pensions that went on during its lean years came back to haunt HSBC many years later.

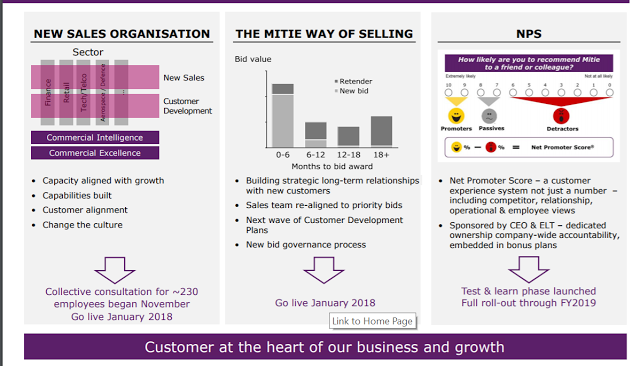

Just how desperate Mitie is for sales quickly becomes evident in the presentation:

A major corporation resorting to customer satisfaction scorecards as a key sales driver is surely a sign that all is not well.

But why has Mitie become so desperate for new sales?

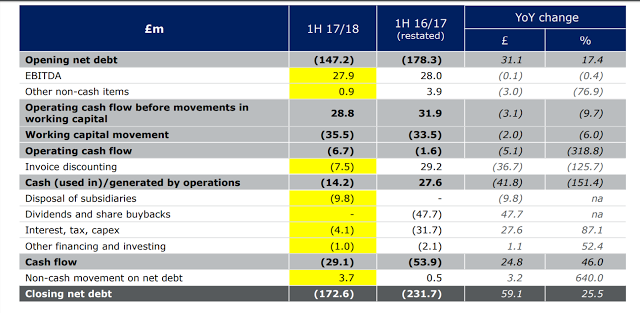

The 2017 interim cash flow statement shows us why:

Cash flow from operations for the half year is negative £14.2 million, and net debt has started to rise again after falling since the profit warning in September 2016. This is not sustainable. Somehow, Mitie must generate more cash. Hence the desperate sales push.But why has cash flow become negative? Even in 2016, when Mitie was scattering profit warnings like confetti, cash flow from operations was positive. What has gone wrong?

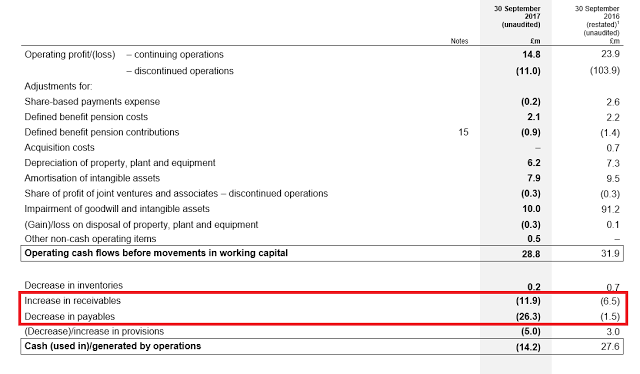

The full cash flow report shows that the negative cash flow is entirely due to changes in payables and receivables:

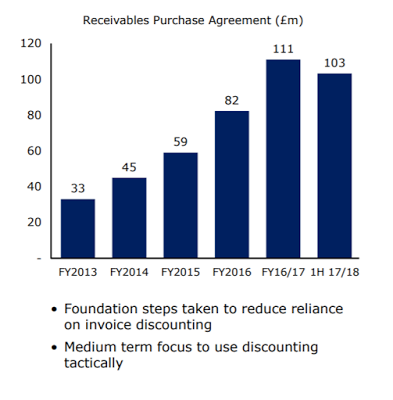

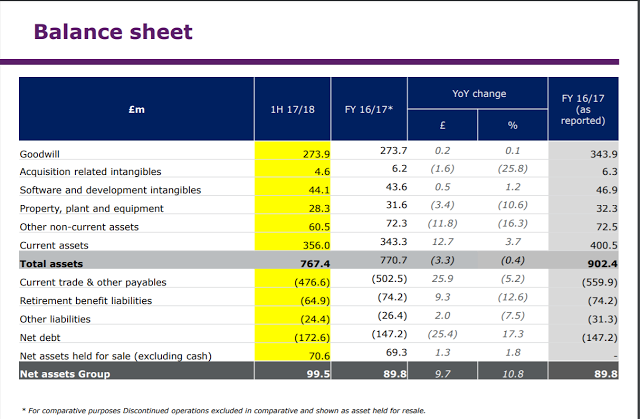

Mitie, it seems, is having trouble extracting money from its customers. This chart, and the accompanying commentary, shows just how bad the situation is: The interim report says that Mitie intends its customer payment terms to be less generous in future, and to that end has unwound part of its invoice discounting facility. Tightening the screws on its customers will eventually flatter its cash flow - if it works. In the short term, though, unwinding the invoice discounting has caused a cash flow hit.The principal cause of the negative cash flow, however, is a fall in trade credit of some £25m. This is a pretty modest fall compared to the size of the accounts payable liability on Mitie's balance sheet:

At the end of September 2017, Mitie owed its suppliers nearly half a billion pounds, more than twice its net debt to lenders. If Mitie's suppliers really flexed their muscles, Mitie would be in big trouble.Mind you, it is probably not in suppliers' best interests to do that. Like other outsourcers, Mitie has little in the way of tangible assets. The biggest assets on its balance sheet are goodwill and receivables (current assets). Goodwill evaporates on insolvency, and receivables may or may not be recoverable. If Mitie failed, creditors - including suppliers - would whistle for their money.

The sharp-eyed among you will notice that there is also a pension deficit of £64.9 million. Although it says it has agreed a 10-year recovery plan with the trustees, Mitie has no chance of closing that deficit while its cash flow is negative. Pension trustees have little choice but to accept that closing the pension scheme deficit is totally dependent on the company developing a healthier and more sustainable financial position.

After Carillion, however, pension trustees may be less willing to tolerate sustained deficits when companies are declaring dividends. Despite negative cash flow, rising net debt and a sizeable pension deficit, Mitie declared an interim dividend of 1.33p in September 2017, probably as a signal to shareholders that it was on the mend after the 2016 "annus horribilis". But it may not be able to take such a liberty again. The Pension Protection Fund was never intended as licence for companies to prioritise dividends for shareholders over returns to their current and future pensioners.

The truth is that Mitie is highly indebted, highly leveraged (equity is less than 10% of total assets) and desperately short of cash. And although it has managed to cobble together a reasonable profit, on its more complex contracts it has done so using the flawed percentage-completion method, which can overstate both profits and net cash flow on contracts where costs are front-loaded. This will be outlawed under IFRS 15, which Mitie must adopt at the latest for its interim 2018 accounts. Capita has already adopted IFRS 15 at the cost of an operating profit write-down of £150m and £1.2bn hit to net assets. It is hard to see that Mitie will fare any better.

To add to its woes, in December 2017 Mitie failed to sell the property management division that it had optimistically moved into "discontinued operations" in its interim accounts. Disposing of indebted business lines encumbered with pending litigation is not that easy, it seems - at least, not at a price that makes a significant dent in net debt. I guess Mitie doesn't want a repeat of the ignominious healthcare disposal for a nominal £2 consideration with a £9.5m sweetener that it was forced to make in March 2017. But it is not clear what it will do with the property management business now.

Shareholders are already seeing the writing on the wall. The share price has been falling since September 2017, and the fall has accelerated since Carillion's collapse:

It seems investors are unconvinced by management plans. So am I. The September 2017 presentation was hilariously bad. Surely people who earn telephone-digit salaries could reasonably be expected to put together something more convincing than that?

Mitie's management cannot continue to string stakeholders along with promises of jam tomorrow when all the indicators are that jam will be in short supply across the entire industry. Nor can it rely any more on an implicit guarantee from government. Mitie needs more capital and much less debt. And above all, it needs a management that will make hard decisions about what the business is really about. In other words, it needs radical reform - before it is too late.

Related reading:

After Carillion, Capita's Profits Warning Comes As No Surprise - Forbes

Cleaning out Carillion's cupboards

Carillion's Failure: The Many Questions That Need Answers - Forbes