Silvergate Bank died yesterday. Its parent, Silvergate Capital Corporation, posted an obituary notice (click for larger image):Silvergate Bank bled to death after announcing significant delay to its 10-K full-year accounts and warning that it might not be able to continue as a going concern. We will never know whether it could have recovered from the bank run after the failure of FTX. The bank run after the announcement was far, far worse. The exit of its major crypto customers sealed Silvergate's fate. But the agent of death was a government agency. On 7th March, Bloomberg reported that Silvergate Bank had been in talks with FDIC about a potential resolution "since last week". Many of us had expected FDIC to go into the bank last Friday with a view to resolving it over the weekend. We

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: banks, Capital, crypto, liquidity, safe assets, Silvergate

This could be interesting, too:

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

merijn knibbe writes The incredible cost of Bitcoin.

Angry Bear writes Crypto’s 5 million campaign finance operation filled airwaves with ads

Bill Haskell writes FDIC: Number of Problem Banks Increased in Q1 2024

Silvergate Bank died yesterday. Its parent, Silvergate Capital Corporation, posted an obituary notice (click for larger image):

Silvergate Bank bled to death after announcing significant delay to its 10-K full-year accounts and warning that it might not be able to continue as a going concern. We will never know whether it could have recovered from the bank run after the failure of FTX. The bank run after the announcement was far, far worse. The exit of its major crypto customers sealed Silvergate's fate.

But the agent of death was a government agency. On 7th March, Bloomberg reported that Silvergate Bank had been in talks with FDIC about a potential resolution "since last week". Many of us had expected FDIC to go into the bank last Friday with a view to resolving it over the weekend. We now know that FDIC did indeed go into the bank, but a resolution over the weekend wasn't possible. Presumably, this means there was no buyer.

Why do I say there was no buyer? Because Silvergate Capital Corporation has put its bank into voluntary liquidation. Liquidation means it is a "gone concern". There's no prospect of resurrection and the best that can be hoped for now is extraction of value from the bank's remaining assets. Silvergate says it intends to repay deposits "in full", but it's not yet clear that it will actually be able to do this. We know that the securities portfolio that ostensibly backs the remaining deposits has fallen considerably in value. Whether sales of the bank's other assets will be sufficient to make good all uninsured depositors remains to be seen.

No doubt FDIC did try to find a buyer. That's how it usually resolves failing banks. And the little that journalists managed to get out of FDIC officials and Silvergate employees suggests that for a while, they had some hope. FDIC probably tried to persuade other banks and financial institutions to take on this deeply distressed bank as a going concern. There was even talk of a crypto industry buyout, though this was never a credible solution for a regulated bank with a Fed master account. But it seems no-one was interested, at least at a price that Silvergate Capital would accept. And hedgies and distressed debt specialists no doubt saw more value in the bank's assets than they did in the business. Vultures prefer their meat to die before they pick its bones clean.

Incredibly, Bloomberg said crypto investors might help the bank "shore up its liquidity". But liquidity isn't a solution to a solvency problem. Like FTX, Carillion, RBS and all the other companies that have desperately called for more liquidity while going down in flames, Silvergate Bank is insolvent. Deeply so. And has been for some time.

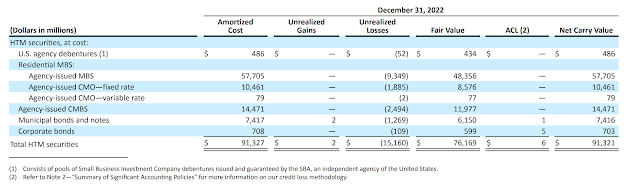

The death of Silvergate Bank should give other banks pause for thought. Silvergate is far from the only bank that is backing volatile demand deposits with government securities that are falling in value as central banks raise interest rates. Silicon Valley Bank, for example, is currently backing demand deposits with a held-to-maturity securities portfolio that at the end of December 2022 was underwater to the tune of over $15 billion - no, this is not a typo, the figures in this table are in millions (click for larger image):

As we saw with Silvergate, fair value losses can be concealed by means of accounting devices such as classing securities as held-to-maturity and carrying them at amortised cost. In 2021, Silicon Valley Bank moved securities with a carry value of $8.8 billion from available-for-sale to held-to-maturity.

Unrealised fair value losses on assets marked as available-for-sale are reported in "other comprehensive income" on the income statement. They don't affect headline profits, but they do affect the bank's capitalisation. If these unrealised losses exceed shareholders' equity, the bank is technically insolvent. In its December 2022 full-year accounts, Silicon Valley Bank reported unrealised losses of $1.911 billion.

But unrealised fair value losses on assets marked as held-to-maturity are not reported in the income statement. In fact they are not reported anywhere except in the notes to the accounts. So they don't affect the bank's capitalisation.

This is fine as long as the bank doesn't experience a liquidity crisis. When a bank needs liquidity, it pledges or sells securities on the open market or at other banks (including the Federal Home Loan Bank and the Federal Reserve) for cash. Selling securities crystallises fair value losses, and as we saw with Silvergate, standing ready to sell securities to meet an unknown volume of deposit withdrawal requests forces the bank to mark its held-to-maturity assets as available-for-sale. As a result, the fair value losses on held-to-maturity assets immediately go through the income statement: realised losses are deducted from headline profits, and all losses, realised and unrealised, are deducted from shareholders' equity.

Silicon Valley Bank's total shareholders' equity is $16.995 billion. So even if it had to move all its held-to-maturity securities to available-for-sale, and take $15bn of accumulated fair value losses through the income statement, it would still be solvent. But this wouldn't leave a great deal of headroom for other losses. So Silicon Valley Bank has now decided to shore up its equity with a $2.25bn stock sale.

But there's another problem. A bank can't raise more cash than the market value of the securities it is selling, and if it is pledging securities, it will raise less. So if the market value of the securities is less than the value of the deposits they are backing, the bank may be unable to raise the money it needs to honour deposit requests. Silicon Valley Bank is is already suffering significant deposit outflows. It could be in deep trouble if this became a full-scale flood. (Though right now, the tanking share price seems to be a more immediate concern...)

Silicon Valley Bank is far from the only bank whose solvency and liquidity are both compromised by rising yields on government securities. In fact smaller banks that are currently permitted to opt out from including unrealised losses on available-for-sale securities in regulatory capital calculations are most exposed.

The lesson from this is that banks should refrain from concealing fair value losses on securities that they might need to sell to obtain liquidity, and regulators should not permit banks that have a high proportion of runnable deposits to mark large parts of their securities portfolios as held-to-maturity in order to avoid taking unrealised fair value losses through P&L. The liquidity risk is far too great.

Furthermore, when asset prices are falling, all banks should shore up their capital buffers to protect creditors from the risk of losses. If they don't do this, there is an enhanced risk of bank runs as people start to question their solvency. And regulators need to change their practices so they are not fooled by apparently healthy capital ratios arising from zero-weighting of government securities and AOCI opt-outs. Silvergate's Tier 1 capital ratio exceeded 50% at the time of its failure - but it was nevertheless deeply insolvent.

When both liquidity and solvency are compromised because of falling asset values, inadequate equity buffers and imprudent accounting practices, banks can literally bleed to death. That's what happened to Silvergate. Those who say that Silvergate's failure was a crypto industry problem are entirely missing the point. Yes, it was runs on crypto platforms that brought Silvergate down, but the underlying fragility was of its own making. What happened to Silvergate could happen to a lot more banks if they don't change their ways.

Related reading:

Lessons from the disaster engulfing Silvergate Bank

Silicon Valley Tank(s) - FT Alphaville

Twitter thread on Silicon Valley Bank from @RagingVentures

Silicon Valley Bank's 10-K report December 2022 can be downloaded here. It makes interesting reading, but I recommend the FT's excellent reporting on what is going on at SVB. I've just used it in this piece as a timely example of solvency and liquidity risk in a much larger bank than Silvergate.