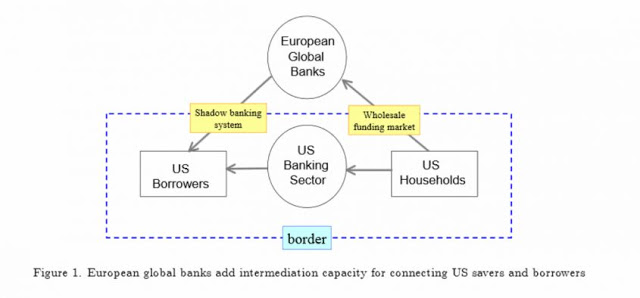

In a lecture presented at the 2011 IMF Annual Research Conference, Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University argued that the driver of the 2007-8 financial crisis was not a global saving glut so much as a global banking glut. He highlighted the role of the European banks in inflating the credit bubble that abruptly burst at the height of the crisis, causing a string of failures of banks and other financial institutions, and economic distress around the globe. European banks borrowed large amounts of US dollars through the money markets and invested them in US asset-backed securities via the US's shadow banking system. In effect, they acted as if they were US banks, but in Europe and therefore beyond the reach of US bank regulation. This diagram shows how it worked (the “border” is the

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Banking, euro, Financial Crisis, Pieria, regulators, risk, safe assets, safety

This could be interesting, too:

Ken Houghton writes Time for A Few Small Repairs?

Matias Vernengo writes Sharing Central Banks’ costs and profits of monetary policy in the euro area

Angry Bear writes Commercial Interests Lobbying Against Railroad Safety kill Legislation

Matias Vernengo writes Neoliberalism Resurgent in Argentina

In a lecture presented at the 2011 IMF Annual Research Conference, Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University argued that the driver of the 2007-8 financial crisis was not a global saving glut so much as a global banking glut. He highlighted the role of the European banks in inflating the credit bubble that abruptly burst at the height of the crisis, causing a string of failures of banks and other financial institutions, and economic distress around the globe. European banks borrowed large amounts of US dollars through the money markets and invested them in US asset-backed securities via the US's shadow banking system. In effect, they acted as if they were US banks, but in Europe and therefore beyond the reach of US bank regulation. This diagram shows how it worked (the “border” is the residency border beyond which US bank regulation has no traction): But it is not the model itself so much as Shin's remarks about the role of European regulation after the introduction of the Euro that interest me:

Why was it Europe that saw such rapid increases in banking capacity, and why did European (and not US) banks expand intermediation between US borrowers and savers? Two likely elements of the answer to both questions is the regulatory environment in Europe and the advent of the euro. The European Union was the jurisdiction that embraced the spirit of the Basel II regulations most enthusiastically, while the rapid growth of cross-border banking within the eurozone after the advent of the euro in 1999 provided fertile conditions for rapid growth of the European banking sector.So there we have it. Forget Asian savers, the yen carry trade, Wall Street excesses. The 2007-8 financial crisis was all the fault of European policy makers and regulators.The permissive bank risk management practices epitomized in the Basel II proposals were already widely practised within Europe as banks became more adept at circumventing the spirit of the initial 1988 Basel I Accord. Basel II was subsequently codified most thoroughly in the European Union through the EU’s Capital Adequacy Directive (CAD). In contrast, US regulators have been more ambivalent toward Basel II, and chose to maintain relatively more stringent regulations (at least, in the formal re gulated banking sector) such as the cap on bank leverage.

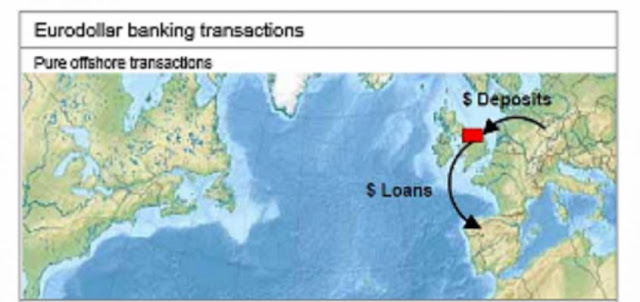

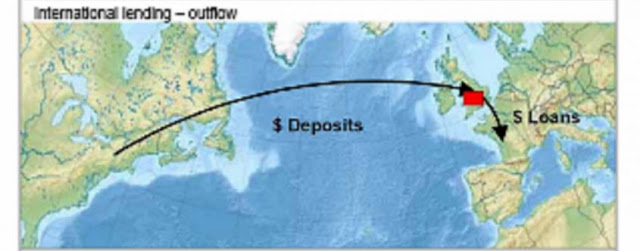

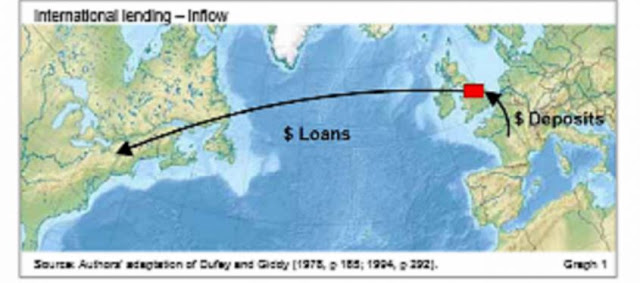

There is no doubt that the Eurodollar market played a sizeable role in the financial crisis. In this paper, Dong & McCauley of BIS show how the flows of dollars across the Atlantic changed from 1999 to 2007. These graphics show the four types of Eurodollar transaction: pure offshore transactions, round-tripping across the Atlantic, US investment in Europe, European investment in the US:

The pure offshore transaction is the most common type of Eurodollar transaction. But during the period 1999-2007, there was a considerable increase in the second type, round-tripping across the Atlantic. These transactions can be driven by regulatory arbitrage:

If domestic deposits attract reserve requirements or incur deposit insurance premiums or pay yields that are capped by interest rate regulation, then depositors willing to hold a deposit in a Caribbean or London branch of a familiar bank can avoid such costs or regulations and receive a higher yield.This appears to support Shin's argument that lax regulation in Europe attracted inflows of funds from the US. But Dong & McCauley also give an alternative explanation:

Round-tripping can also involve important credit intermediation in which a non-US bank puts its capital at risk. In the 2000s, as we shall see below, European banks attracted dollar funding from risk-averse US residents in order to finance holdings of ultimately risky US asset-backed securities at what seemed to be attractive spreads.This is not regulatory arbitrage, it is interest rate arbitrage. Money market funds would lend to European banks because they could get better rates than from US banks. But why were European banks offering higher rates on US deposits than US banks?

The first reason could be the low interest rate environment in the US in the early 2000s. The Fed Funds rate was several percentage points below both the UK base rate and the ECB's refi rate, a difference that was not entirely lost in the exchange rates. European banks might therefore be expected to offer better US dollar rates on deposits than US banks. But we know that banks in Europe also borrowed and lent huge amounts of Euro and sterling at this time, feeding real estate bubbles in the UK, Ireland and Spain and sovereign debt bubbles in Greece and Italy. If covered interest rate parity only weakly held during this time, low US rates might have encouraged European banks to fund themselves in US dollars for lending in Euro and Sterling. But this wouldn't explain the increase in round-tripping.

The second reason, according to Shin, is the introduction of the Euro. The single currency removed exchange rate risk in cross-border lending between Eurozone countries, which undoubtedly encouraged large Eurozone banks to lend excessively to both the private and public sectors in Eurozone periphery countries. The Eurozone crisis can indeed be partly laid at the door of the single currency, for this and other reasons. But it is difficult to see why the introduction of the Euro would have encouraged European banks to load up with US securities. They could do so even without the Euro: the UK is not a member of the Euro, but the UK banks were among the most significant contributors to the Eurodollar lending glut.

To my mind the most likely explanation is the US's securitization engine. US banks, whose lending Shin correctly notes was limited by a leverage ratio, did not keep loans on their balance sheets. They sold them, and used the proceeds to fund further lending. Northern Rock and HBOS in the UK used similar “lend-securitize-fund” models. While the securitization engine was working well, as it was in the early 2000s, banks that used this model did not have an enormous need for wholesale funds. Most of their lending was funded by the proceeds from securitizations. They would therefore be unlikely to offer good rates to US money market funds. It was not until the securitization engine started to slow in 2006 that banks using this model started to need larger amounts of US dollar funding and rates started to rise.

So US banks unloaded their loans into warehouses for securitization and sale. And once they left the balance sheets of regulated banks, they were outside US regulatory jurisdiction, as Shin's diagram shows. There was effectively no regulation of the process of securitization and sale. Investment banks created exotic products from packages of warehoused loans, obtained high credit ratings for them from captive ratings agencies, and sold them into the global capital markets, where they were snapped up by – among others – European banks.

Shin rightly notes that the European banks were not subject to the US's leverage ratio. Instead, they had Basel II's capital ratio. And because these exotic securities were routinely rated AAA, their effect on European banks' capital requirements was negligible. They could load up to the skies with these things with virtually no capital allocation. In this, Shin is correct. Had European banks been subject to a leverage ratio, they would not have been able to load up on toxic US credit derivatives, and the course of history might have been very different.

But I think it is unfair to lay the responsibility for the growth of the US dollar “banking glut” solely at the door of European regulations. After all, it was the tight regulation of US banks that forced them to sell their loans. It would be more accurate to say that the combination of a leverage ratio in the US and a capital ratio in Europe caused the creation of what we might describe as a “pump”. US banks were looking for a marketplace into which to sell loans that they couldn't keep on their balance sheets, while European banks were looking to buy safe assets that had minimum capital requirements and gave good returns. The industry that grew up to service both sides was the unregulated “shadow” banking industry. The incentives for this industry to misprice risk are clear.

And there is another dimension to this that Shin does not discuss. His diagram suggests that “US households” were the suppliers of funding to both US banks and – via money market funds – to the European banks. But where did these US households get their money? After all, US wages have been stagnating for two decades.

The answer is not, as Bernanke would have it, Asian savers. It is far more toxic. Shin's diagram is a “loanable funds” model, where banks take in deposits and loan a proportion of them out. But that is not how lending works. The reality is far more complex. In the next two paragraphs, if you get confused, remember this: “Loans create deposits, and deposits fund loans”.

The US banks created new deposits when they lent against property. Those deposits transferred to the sellers of property, who put that money into money market funds which then lent the money on to European banks. Meanwhile, the US banks sold their loans to the shadow banking industry, which in turn sold the securities created from those loans to European banks. So in effect, the US banks provided the European banks with the funds to buy their securities.

But there was also a credit creation process going on at the European end. Banks don't just create money when they lend – they create money when they buy securities, too. After all, it is only another form of lending. That money found its way back through the shadow conduits to the US banks, which used it to fund their loans. So the European banks also provided the US banks with funding for lending. There was in fact a two-way flow of funding. No wonder leverage increased so so much and so quickly.

It is those flows of funds that dried up in the financial crisis. We could say that the “pump” failed. When the heart stops beating, the patient quickly dies.....

So what should we learn from this?

Neither US nor European banks thought they were “taking excessive risks”. On the contrary, both sides were looking for safety. US banks were prudently removing loans from their balance sheets in order to remain within their Basel 1 leverage constraints. And European banks were prudently looking for safe assets that gave good returns. Not only that, but the shadow institutions that pumped the lending and the funding from the US to Europe and back again also thought they were acting prudently. After all, the securities were backed by the US property market, which had not suffered a major fall since the 1930s. And the US dollar deposits were backed by the US government.

The story of the financial crisis is a story of the failure of safe assets. That is why it was so traumatic. People expect to take losses on risky investments. They don't expect to take losses on safe ones. Yet we are still trying to make the financial system “safer” and encourage investors to invest in “safe” assets. When will we learn that the safest investment is a risky one, and the most dangerous investments are those that are believed to be completely safe?

And it is also a warning of the consequences of regulatory arbitrage. The fact that the US and European banks had different regulatory regimes created a golden opportunity for unregulated institutions to exploit, with catastrophic consequences. Yet the US, the UK and the EU are still devising their own systems of regulation with scant regard for international consistency. When will we learn that an international industry requires international regulation?

Related reading:

Financial hurricanes

Financial hurricanes - lecture given for Brave New Europe in Berlin, February 2019 (Youtube video)

On risk and safety

The illusion of safety

This post originally appeared on Pieria in October 2014. The header image is from the original Pieria post.