Summary:

There's yet another bizarre claim doing the rounds in Waspiland. Or, more correctly, among the hardline Back to 60 fringe of the broader women's state pension movement. I try to ignore most of the ridiculous claims made by Back to 60 campaigners, because they aren't going to listen to me and I will simply end up with a sore head and a very frayed temper. But this one is more complex - and confusing - than most, and it doesn't only affect women. So it is worth explaining. As always, the story starts with the unequal state pension ages of men and women. When the present state pension system was introduced in 1946, women's state pension age was set at 60, and men's was 65. To qualify for a full state pension, women had to make 39 years of NI contributions: because their state pension age was

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: discrimination

This could be interesting, too:

There's yet another bizarre claim doing the rounds in Waspiland. Or, more correctly, among the hardline Back to 60 fringe of the broader women's state pension movement. I try to ignore most of the ridiculous claims made by Back to 60 campaigners, because they aren't going to listen to me and I will simply end up with a sore head and a very frayed temper. But this one is more complex - and confusing - than most, and it doesn't only affect women. So it is worth explaining. As always, the story starts with the unequal state pension ages of men and women. When the present state pension system was introduced in 1946, women's state pension age was set at 60, and men's was 65. To qualify for a full state pension, women had to make 39 years of NI contributions: because their state pension age was

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: discrimination

This could be interesting, too:

Frances Coppola writes The true story of NI autocredits

Mike Norman writes Jason Smith — Women in the workforce and labor shar

Jeff Mosenkis (IPA) writes IPA’s weekly links

Jeff Mosenkis (IPA) writes IPA’s weekly links

As always, the story starts with the unequal state pension ages of men and women. When the present state pension system was introduced in 1946, women's state pension age was set at 60, and men's was 65. To qualify for a full state pension, women had to make 39 years of NI contributions: because their state pension age was 5 years later, men had to make 44 years of contributions.

During the inflationary 1970s, unemployment gradually rose to the highest levels since the Great Depression. Youth unemployment was particularly high, and for the first time, graduates were affected. Concerned by rising youth unemployment, in 1977 the Labour government introduced a job release scheme (JRS) for older employees, both men and women. Originally, it was limited to employees within one year of state pension age - ie 59 for women and 64 for men - and was conditional on the firm employing someone from the unemployment register to replace them. But by the mid-1980s it had been extended to all men over 60, and the conditionality had been lifted.

The JRS paid a flat-rate allowance to people who took early retirement under the scheme. The allowance was significantly lower than the median income, but 70% higher than unemployment benefit and 40% higher than the basic state pension. It was attractive to those on low incomes, those who could supplement it with an occupational pension, and those who would otherwise lose their jobs. But there was one huge problem. It did not include NI credits. Unless they registered as unemployed, people who retired early could find themselves with a lower state pension when they reached state pension age.

In March 1983, the Chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, announced that the JRS would be extended to men over 62 and women over 59 who wished to reduce their hours:

I can now announce a new scheme for part-time job release. It will apply to the same categories of older people who are willing to give up at least half their standard working week, so that someone else who is without a job can be taken on for the remaining half. The allowances will be paid at half the full-time rate. The scheme will take effect from 1 October and should provide part-time job opportunities for up to 40,000 more people who are at present unemployed.

Simultaneously, Howe announced that men over 60 who were not working, including those who had taken early retirement under the JRS, would no longer have to register as unemployed in order to receive NI credits:

Some 90,000 men between the ages of 60 and 65 now have to register at an unemployment benefit office if they wish to secure contribution credits to protect their pension rights when they reach 65. From April, they will no longer have to do this. Even if those concerned subsequently take up part-time or low-paid work on earnings which fall below the lower earnings limit for contributions, their pension entitlement will be fully safeguarded.

So the NI contributions of men aged over 60 would in effect be guaranteed by the state.

Why did these "autocredits" only apply to men? Simple. Women could take their state pensions from 60, whereas men had to wait until 65. And men also needed 44 years of NI contributions to qualify for a full state pension, whereas women only needed 39. So only men were suffering from loss of pension rights due to retiring in their early 60s.

It could be argued that women suffered a similar loss of state pension rights if they retired between 55 and 59. But the JRS scheme did not encourage them to do so. The autocredits were introduced because government policy at that time specifically encouraged men - but not women - to take early retirement some years before their state pension age.

It could also be argued that it was harder for women to make enough NI contributions, because they tended to have long breaks from work, work part-time and be paid less than men. However, none of this was considered at the time. And as we shall see, it became irrelevant as far as women born in the 1950s are concerned.

In 1995, legislation was passed to raise women's state pension age gradually to that of men, starting in 2010 and completing in 2020. As a consequence of this legislation, women would have to make the same NI contributions as men. Clearly, therefore, if men in their early 60s received automated NI credits, so too should women affected by the state pension age rises. In a letter sent to Myfanwy Opeldus in 2002, the DWP indicated an intention to extend autocredits to women:

At the moment, we award National Insurance credits to men between the ages of 60 and 65 who don't work and don't pay National Insurance contributions. We do this to protect their basic State Pension entitlement. We will make similar arrangements for women from 2010, when their State Pension age begins to rise.

In 2007, the Labour Government cut the number of years of NI contributions required for a full state pension to 30 for both men and women. The change would take effect from 2010. As a result, it became much less likely that men retiring in their early 60s from 2010 onwards would not have a full NI contribution record. So, in 2009, the Labour government used a statutory instrument to phase out autocredits from 2010 onwards.

An explanatory memorandum issued with the statutory instrument sets this decision in the context of the 1995 legislation equalising state pension ages. Autocredits had become a concession to men to soften the impact of continuing discrimination against them during the 25 years it would take to complete equalisation. They enabled men to stop work in their early 60s without suffering a state pension penalty:

7.33. Since 1983, National Insurance credits have been automatically available to men to make up any deficiencies in their record in the five tax years before the year in which they reach state pension age. “Autocredits” were introduced alongside changes that meant that men were no longer required to be available for work as a condition for receiving benefit once they reached age 60 (ie. the age at which women become eligible for the state pension). Autocredits protect a man’s basic state pension position during these five years if he is not working and paying National Insurance or entitled to credits for other reasons such as registered unemployed, sick, or a carer.

But autocredits did not give men an early state pension, as some have claimed. If men stopped work in their early 60s, they either had to live on their occupational pensions or, if they were poor, claim the means-tested Pension Credit. Women of the same age were, of course, receiving state pensions.

The memorandum goes on to acknowledge that the original intention had been to extend autocredits to women as their state pension age rose. It notes that under the original legislation, the number of years of NI contributions that women would have to make to qualify for a full state pension would have increased in line with their state pension age:

7.34. When the Government published its plans for state pension age equalisation in 1993, the intention then was that as women’s pension age increased gradually to 65, autocredits would become available to them on the same basis as for men. This was in part to compensate for the increase in the number of years women would otherwise have to pay National Insurance contributions for in order to qualify for a full basic pension.

And it then explains the reasons for the decision to phase out autocredits:

7.35. This approach has since been reviewed, for two reasons. Firstly, the qualifying age for Pension Credit (the income-related benefit currently payable to men and women at 60 without jobseeking conditions attached) is set to increase to 65 by 2020 in line with female state pension age. Men claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance or Employment and Support Allowance will no longer have the option of switching to Pension Credit in the run-up to state pension age and will continue to receive a credit through receipt of those benefits instead. Without the proposed change, autocredits would increasingly apply mainly to people who could afford not to work or claim benefit. Secondly, the reduction in the number of qualifying years needed for a full basic pension to 30 and the improvements in the crediting arrangements for carers under the measures introduced by the Pensions Act 2007 will mean that the need for autocredits to protect state pension entitlement will be significantly reduced. (Those who would have benefited from autocredits had they been available will still have the option of paying voluntary National Insurance contributions to make up “missing years”.)

In short, as sex discrimination in state pension ages was progressively eliminated from 2010 onwards, the concessions made to men to soften the impact of that discrimination would be gradually withdrawn, rather than extended to women as well. Once state pension ages were equalised, both men and women aged 60-64 who were not working would have to rely on the working-age benefits system rather than any form of state pension provision. Those who qualified for working-age benefits would receive the NI credits associated with those benefits.

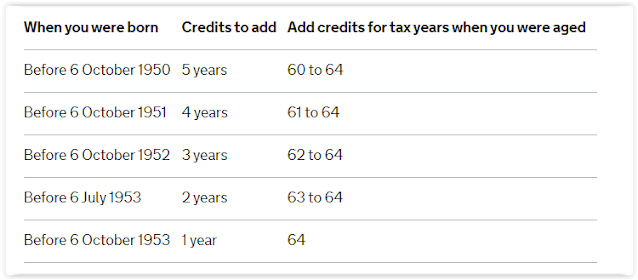

Autocredits were to be phased out gradually between 2010 and 2020. As women's state pension age rose, the age at which men became eligible for autocredits would also rise, thus ensuring that men only received autocredits for the period during which women of their age were receiving state pensions but they were not:

7.36. This instrument amends the Credits Regulations to provide that autocredits will be available to men only for the tax years in which they have reached what would be pension age for a woman of the same age, up to and including the last tax year before the one in which they reach age 65. Men born on 6 October 1954 or later, who will reach both female pension age and their own state pension age in the same tax year, will not qualify for the credits.

The timetable was accelerated in 2011 in line with the timetable for women's state pension age rises. Autocredits were eliminated completely in November 2018, when women's state pension age reached 65.

However, the taper was considerably simpler than that for womens' state pension age rises:

(for comparison, you can find the timetable for women's state pension age rises under the 1995 Pensions Act here and the accelerated timetable under the 2011 Pensions Act here)

Because of this, some men will have received autocredits for short periods before women of their age reached state pension age. But we don't even know how many men received autocredits between 2010 and 2018, let alone how many of those received autocredits while women of their age were still working. All we have is a Freedom of Information response that tells us that between 1983 and 2018, as some 4.6m men may have qualified for autocredits. However, many of those men didn't need autocredits to qualify for a full state pension, either because they had already made enough NI contributions or because they were still working and paying NI. And some of the men died before reaching state pension age. So the truth is we have no idea how many men benefited from NI autocredits. It may not be very many.

But of one thing we can be certain. Whether or not they benefited from NI autocredits, all of those 4.6m men were victims of statutory sex discrimination. They lived at a time when women of their age had earlier state pension ages than they did. Now, that discrimination has been eliminated, and with it the concessions such as autocredits that aimed to made it bearable. They are no longer needed by men, and they were never needed by women. What is needed now, as I have explained before, is reform of working-age benefits to make them less harsh and more suitable for both men and women as they approach retirement.

Related reading:

Social Security (Age of Retirement) Bill - Hansard