"The euro area economy is gradually emerging from a deep and protracted downturn. However, despite improvements over the last year, real GDP is still below the level of the first quarter of 2008. The picture is more striking still if one looks at where nominal growth would be now if pre-crisis trends had been maintained." So said Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, in a recent presentation to the FAROS Institutional Investors' Forum.He's not wrong. From his presentation, here is a chart showing the difference between current output, current (estimated) potential output and projected output prior to 2007: That is indeed a striking gap. It is reflected in this chart from Eurostat (August 2015): So, the fall in GDP growth between 2007 and 2015 has resulted in a rise in unemployment of nearly 4 percentage points. Currently, across the Euro area as a whole (population about 340m), adult unemployment stands at 11% and youth unemployment about twice that. That is a LOT of wasted lives.Since 2008, the Euro area has experienced a severe, extended double-dip recession from which it has not yet emerged: Comparisons with previous recessions in Euro area countries (prior to the formation of the Euro, of course), as well as to the US's 2009 recession, show just how severe and prolonged this recession has been. It is probably reasonable to call it a depression.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: depression, ECB, Eurozone, Financial Crisis, GDP, inflation, recession, recovery, Unemployment

This could be interesting, too:

Matias Vernengo writes Serrano, Summa and Marins on Inflation, and Monetary Policy

Angry Bear writes Voters Blame Biden and Harris for Inflation

Angry Bear writes GDP Grows 2.3 Percent

Lars Pålsson Syll writes How inequality causes financial crises

So said Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, in a recent presentation to the FAROS Institutional Investors' Forum.

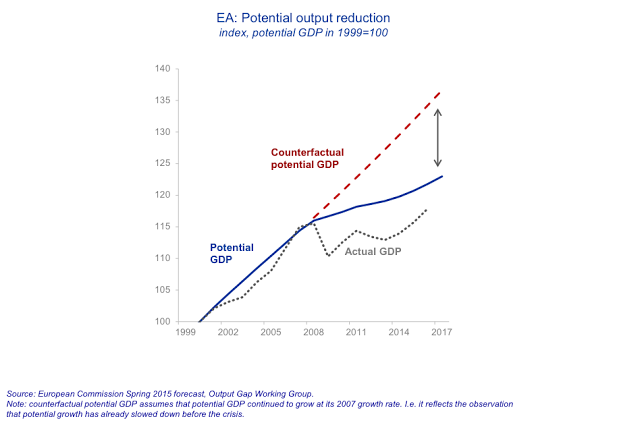

He's not wrong. From his presentation, here is a chart showing the difference between current output, current (estimated) potential output and projected output prior to 2007:

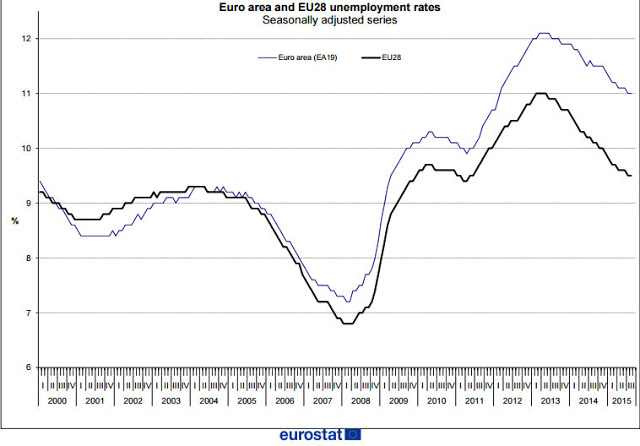

That is indeed a striking gap. It is reflected in this chart from Eurostat (August 2015):

So, the fall in GDP growth between 2007 and 2015 has resulted in a rise in unemployment of nearly 4 percentage points. Currently, across the Euro area as a whole (population about 340m), adult unemployment stands at 11% and youth unemployment about twice that. That is a LOT of wasted lives.

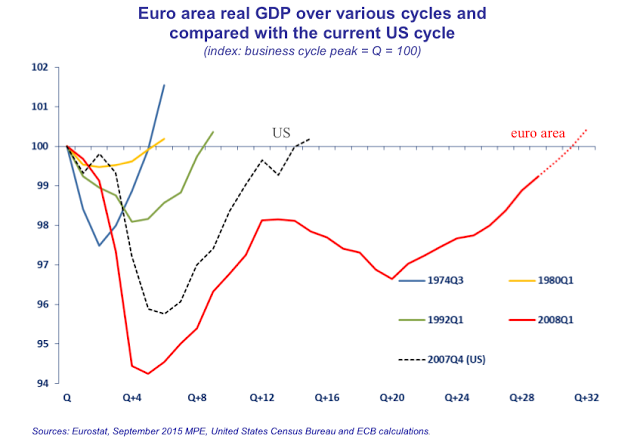

Since 2008, the Euro area has experienced a severe, extended double-dip recession from which it has not yet emerged:

Comparisons with previous recessions in Euro area countries (prior to the formation of the Euro, of course), as well as to the US's 2009 recession, show just how severe and prolonged this recession has been. It is probably reasonable to call it a depression.

If the Euro area continues on the path shown in this chart, it should emerge from depression by the end of 2016. But as Praet observes, the outlook for the global economy is not exactly bright, and the projected recovery path for the Euro area is by no means certain:

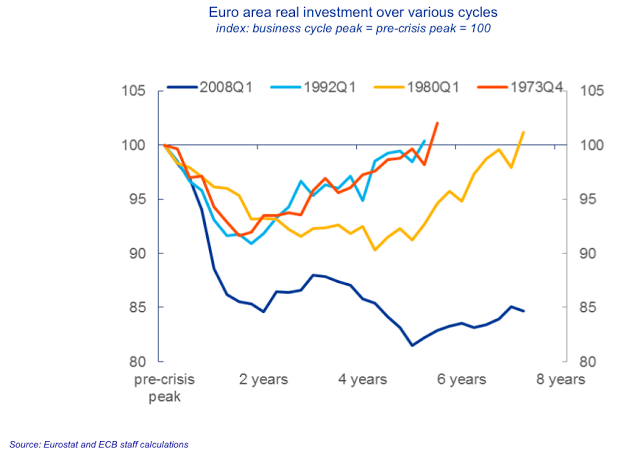

These aren't the only tailwinds supporting the economy. Lending figures from the ECB for September 2015 show continuing weakness in private sector loan demand, largely offset by strong growth of general government borrowing (7.2%, up from 6.3% in August). Despite continuing attempts by Brussels/Berlin to squash government support in the name of "fiscal discipline", it seems that governments are still borrowing to spend - fortunately, since there is little support coming from anywhere else. Investment in the Euro area fell sharply in 2008 and again in 2012, and remains shockingly low: Praet observes that:The risks around the evolution of the global economy have shifted downward, making the contribution of external demand to the recovery less assured. Domestic demand, though rising, also appears relatively weak if one considers that we are still in an early phase of the recovery and that there are important tailwinds supporting the economy – namely our monetary stimulus and lower oil prices.

He goes on to attribute this to the continuing overhang of private and public sector debt, and to the very poor returns on capital in some Euro area countries.investment has so far failed to perform its "accelerator" role for the recovery.

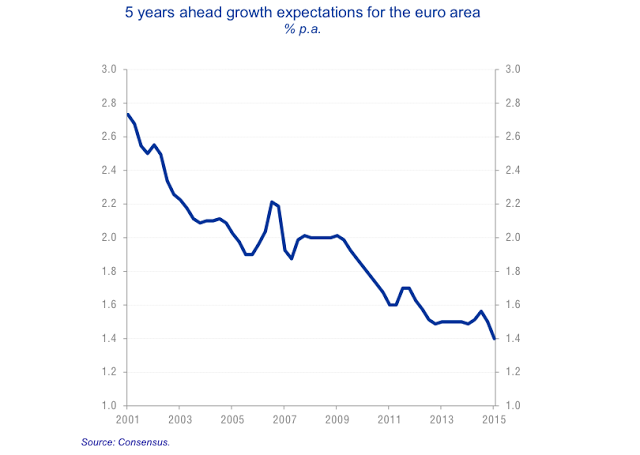

Importantly, Praet also notes that expectations of future growth in the Euro area are declining:

The debt overhang is undoubtedly a cause of the investment chill, but so are the low expectations of investors. After all, if you expect GDP growth 5 years hence to be a measly 1.4%, why would you bother to invest?

This is, of course, one of those nasty feedback loops that complicate macroeconomic forecasting. Low expectations cause low investment, which in turn depresses future growth prospects, causing expectations to fall further. It seems unlikely that private sector investment will improve any time soon. And because of this, inflation is unlikely to rise. This is therefore a matter of some concern to the ECB. Inflation (HICP) is currently far below target, and the latest ECB forecast predicts an extremely slow return to target - more than two years. Praet comments that inflation expectations are being affected by short-term supply-side effects (low oil prices), which suggests that they are becoming "unanchored" on the downside. Putting the two together, people expect growth to disappoint and inflation to remain below target for the foreseeable future.

Assuming that the Phillips curve remains negatively sloped - i.e. that there is an inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment - expectations of poor growth and very low inflation indicate that unemployment will remain stubbornly high for the foreseeable future.

The Euro area is stuck in a low-growth, low-inflation, high-unemployment equilibrium. It will take one heck of a big bazooka to knock it out of this toxic balance. The countries in the Euro area don't have that kind of bazooka. They are restricted by fiscal rules that make it impossible for them to do the large-scale investment spending that will be needed to restore growth. There is no Euro area federal government that could take on an investment programme of the necessary scale: President Juncker's plan is nowhere near adequate. The ECB is the only player with the necessary firepower, but it is insanely prevented by treaty directive from using its really big guns.

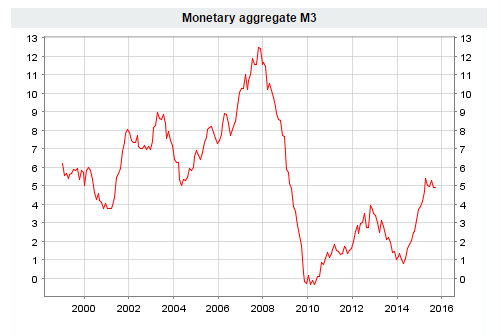

Perhaps predictably, Praet deflects criticism of the ECB for the Euro area malaise, arguing that restoring growth requires "structural reforms" from governments, not a more active role for the ECB. Yet this is the ECB that triggered the double-dip recession by failing to do its job of lender of last resort, allowing the Euro to fragment and sovereign yields to spike due to fears of Euro breakup and redenomination. And although Draghi's "whatever it takes" in 2012 ended fears of redenomination risk, the ECB then allowed M3 growth to fall for over a year, which was completely unwarranted - and very damaging - monetary tightness for an economy as depressed as the Euro area:

source: ECB statistical data warehouseIt is very hard to excuse the ECB for these errors.

It is not reasonable to claim, as Praet does, that restoring growth in the medium term is solely the responsibility of governments. To the contrary, it is extremely difficult for governments to undertake structural reforms when money is unjustifiably tight. M3 growth has improved, but as the chart shows it is now flatlining at the 2004 level. If unemployment and growth were at their 2004 levels, this level of M3 growth would be appropriate. But for a depressed economy with high unemployment, no inflation and a substantial output gap, it is way too low. Further stimulus is unquestionably needed.

Unfortunately there are influential voices arguing not only that further monetary stimulus is not necessary, but that the stimulus applied so far should be removed. For the sake of the unemployed, and those suffering from income restrictions, tax rises and benefit cuts, I hope these siren voices are resisted. The combination of tight money and fiscal restriction entrenches depression and unemployment.

I know I've said this before (and been criticised for saying it), but there is an uncomfortable historical precedent here. A similar toxic equilibrium was reached in certain European countries in the 1930s. It resulted in the rise to power of nationalistic governments, autarky and extremism, and eventually war. I do not forecast this, but we should not forget it. A war is certainly a big bazooka, and as long as people perceive it as politically justified, it is unlikely to be opposed on economic grounds.

But war, however justifiable, is terribly destructive. It would be far better for the Euro area to risk fiscal profligacy and monetary irresponsibility than travel that road again. So let's ditch the ridiculous rules and directives, spend a lot of money - ideally by means of helicopter drops, since increasing the fiscal burden on highly-indebted countries in a dysfunctional monetary union is not a sustainable solution - and get people working, and the economy growing, again.

Related reading:

The Slough of Despond

The dangers of historical taboos

The ECB is not doing its job. Again.

A terrible stability - Pieria

Structural destruction - Pieria