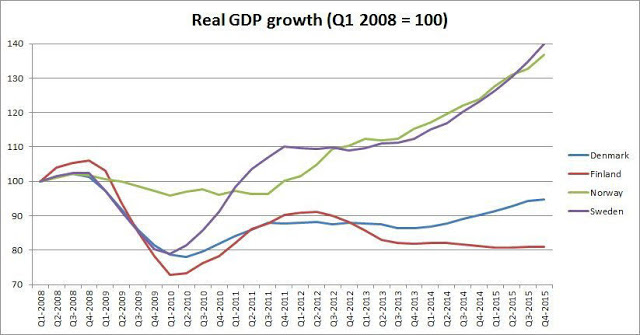

From @MineforNothing on Twitter comes this chart: Now, we know Finland is in a bit of a mess. A series of nasty supply-side shocks has devastated the economy. When Nokia collapsed in the wake of the 2007-8 financial crisis, ripping a huge hole in the country's GDP, the government responded with substantial fiscal support. This wrecked its formerly virtuous fiscal position: it switched from a 6% budget surplus to a 4% deficit in one year, and although its deficit has improved slightly since, it is still outside Maastricht limits. Because of this, the current government - under pressure from the insane Eurocrats - is implementing fiscal austerity to bring the budget deficit back below 3% of GDP. For an economy which has suffered a serious reduction in its productive capacity, this is disastrous. The austerity measures will neither reduce the deficit nor restore the economy. On the contrary, they will cause the economy to shrink and consequently - through simple arithmetic - increase the deficit as a proportion of GDP. Finland has been in recession for just about all of the last four years: what it needs is expansionary fiscal policy, not bloodletting. Austerity is an utterly self-defeating policy for an economy which has a damaged supply side due to exogenous shocks.The one thing that is keeping the Finnish economy from imploding is the ECB's expansionary monetary policy.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Denmark, euro, Eurozone, finland, fiscal policy, GDP, Monetary Policy, Norway, Sweden

This could be interesting, too:

Angry Bear writes GDP Grows 2.3 Percent

Merijn T. Knibbe writes ´Extra Unordinarily Persistent Large Otput Gaps´ (EU-PLOGs)

Angry Bear writes A Fiscal Policy in a Global Context?

Matias Vernengo writes Very brief note on the Brazilian real and the fiscal package

Now, we know Finland is in a bit of a mess. A series of nasty supply-side shocks has devastated the economy. When Nokia collapsed in the wake of the 2007-8 financial crisis, ripping a huge hole in the country's GDP, the government responded with substantial fiscal support. This wrecked its formerly virtuous fiscal position: it switched from a 6% budget surplus to a 4% deficit in one year, and although its deficit has improved slightly since, it is still outside Maastricht limits. Because of this, the current government - under pressure from the insane Eurocrats - is implementing fiscal austerity to bring the budget deficit back below 3% of GDP. For an economy which has suffered a serious reduction in its productive capacity, this is disastrous. The austerity measures will neither reduce the deficit nor restore the economy. On the contrary, they will cause the economy to shrink and consequently - through simple arithmetic - increase the deficit as a proportion of GDP. Finland has been in recession for just about all of the last four years: what it needs is expansionary fiscal policy, not bloodletting. Austerity is an utterly self-defeating policy for an economy which has a damaged supply side due to exogenous shocks.

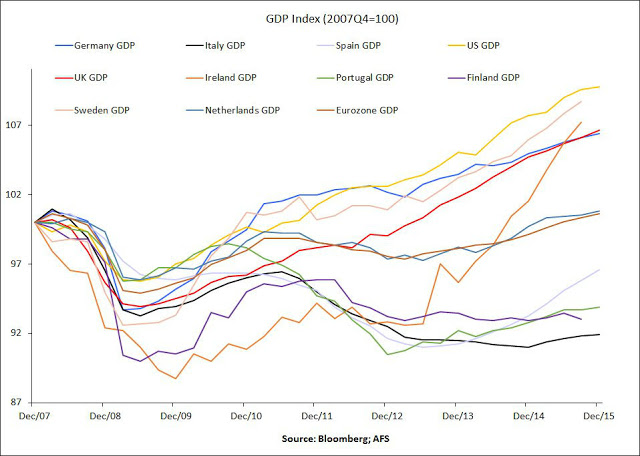

The one thing that is keeping the Finnish economy from imploding is the ECB's expansionary monetary policy. Negative rates and QE may be a weak stimulus, but they are better than nothing. Finland has been masquerading as a prosperous core country, but the truth is that it is much more like the weak Southern European states:

(US GDP is included for comparison)

Without ECB support, Finland would be in deep trouble.

But what on earth has gone wrong with Denmark? Like Finland and Sweden - and interestingly, NOT like Norway (more on that shortly) - Denmark suffered a deep recession after the financial crisis, hitting bottom in the second quarter of 2010. But unlike Sweden, it did not recover. The pattern of its GDP growth is much more like Finland's. Yet it did not have the supply-side shocks that Finland suffered. Why has it stagnated for most of the last seven years?

Every man and his dog has a theory about this. Most of them focus on Denmark's generous welfare state and relatively high taxation. High taxation stifles enterprise, while the welfare state discourages productive work, apparently. So what Denmark should do is cut taxes and shrink its welfare state. That will make it much more prosperous - though probably no happier.

But hang on. Sweden also has a generous welfare state and relatively high taxation. So does Norway. Indeed, so does Finland. All the Nordic states do. And all of them have made serious attempts in recent years to improve the efficiency of their welfare systems and reduce their cost. Denmark, in fact, ranks higher up the OECD's list of countries by reform effort than any other Scandinavian country. Yet their economic performance differs enormously. Finland and Denmark are performing poorly. Norway and Sweden are performing well - and Norway did not suffer the deep recession of the post-crisis years, either. It is hard to see that Scandinavian welfare and taxation causes this. No, there is some exogenous reason.

The reason is not difficult to find. Finland, the worst-performing of these countries, is a member of the Euro. Not only does this prevent it from managing its own monetary policy, including devaluing to protect its economy from exogenous shocks, but it also chains its fiscal policy to the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact. Finland is in the Excessive Deficit Procedure, and as a Euro member, that means it must comply with the actions required under that procedure or face sanctions - even if those actions are directly harmful to its economy.

None of the others is a Euro member. But Denmark is a member of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) which is a precursor to Euro member. It is obliged to maintain the value of its currency within agreed bands around the Euro. Its monetary policy is therefore determined to a large extent not by local conditions, but by the decisions of the ECB - whether or not they are appropriate for the Danish economy. Denmark has also agreed to be bound by the stricter form of the Stability and Growth Pact known as the Fiscal Compact, which means it is subject to the same fiscal rules and penalties as if it were a member of the Eurozone.

In contrast, Sweden is not a member of ERM II. It is supposed to join the Euro at some point, but - mysteriously - persistently fails to meet convergence criteria. The Swedish krona floats against world currencies including the Euro, giving Sweden much greater control of its monetary policy than Denmark or Finland. On the fiscal side, although Sweden ratified the Fiscal Compact, it refused to allow itself to be bound by its provisions while it remains outside the Euro. So although it is supposed to keep within Maastricht fiscal limits, it does not face penalties for failing to do so.

Norway, of course, is not a member of the EU. Since Norway is an oil exporter, the Norwegian krone is a petrocurrency. Norway has used its sovereign wealth fund effectively to mop up the income from oil production and prevent its currency appreciating excessively. Recent oil price falls nevertheless have hit it hard: January's GDP growth was negative, and it is currently drawing on its sovereign wealth fund to maintain fiscal programmes. It remains to be seen whether Norway's previous responsible management will be sufficient to prevent it slipping into outright recession. But Norway's current difficulties are principally due to global conditions, not because of ties to a depressed and austerity-obsessed Eurozone.

The ability to manage monetary and fiscal policy is precious. Eurozone central banks, locked into a one-size-fits-all monetary policy, have little ability to protect their economies from local shocks; with the centralisation of bank supervision, they have even largely lost control of macroprudential policy. Eurozone fiscal authorities, too, have little autonomy once the country is in the Excessive Deficit procedure; for those outside it, avoiding Brussels supervision can become an overriding concern. For Eurozone countries, the real monetary target is not inflation but deficit/GDP. The ECB is fighting a losing battle trying to raise inflation against the determination of the Brussels bureaucracy to force 19 fiscal authorities to depress demand in the name of balancing the books.

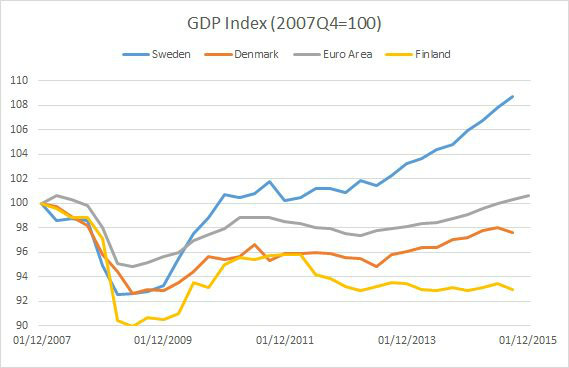

So Finland's economic disaster is at least partly a consequence of its Euro membership. And Denmark suffers from loss of monetary autonomy due to its membership of ERM II, and loss of fiscal autonomy because it chooses to be bound by the Fiscal Compact. Conversely, Sweden has control of both monetary and fiscal policy, while Norway not only has control of monetary and fiscal policy but is further buffered by its large sovereign wealth fund.

The final evidence is provided by this chart:

Related reading:

A Finnish cautionary tale

An unjustified rating

Reforms, bloody reforms