Summary:

In June this year, a company called intu (no capitalisation) collapsed. Most people had never heard of it. But they knew what it did. It was the owner of many of the UK's biggest shopping centres. Lakeside in Thurrock, Metro Centre in Newcastle, and the Trafford Centre in Manchester - all of these were owned by intu. Indeed, they still are. At the time of writing, no disposals have been made. So intu is the landlord of a significant part of the UK's retail sector. And it is dead, killed by the pandemic. But like many of those killed by the pandemic, intu had underlying health issues that made it especially vulnerable. Long before the pandemic struck, the retail sector was in trouble. Over the last few years, a stream of household names have gone to the wall: Woolworths, Toys R Us,

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: coronavirus, Debt, default, insolvency, retail, UK

This could be interesting, too:

In June this year, a company called intu (no capitalisation) collapsed. Most people had never heard of it. But they knew what it did. It was the owner of many of the UK's biggest shopping centres. Lakeside in Thurrock, Metro Centre in Newcastle, and the Trafford Centre in Manchester - all of these were owned by intu. Indeed, they still are. At the time of writing, no disposals have been made. So intu is the landlord of a significant part of the UK's retail sector. And it is dead, killed by the pandemic. But like many of those killed by the pandemic, intu had underlying health issues that made it especially vulnerable. Long before the pandemic struck, the retail sector was in trouble. Over the last few years, a stream of household names have gone to the wall: Woolworths, Toys R Us,

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: coronavirus, Debt, default, insolvency, retail, UK

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

Robert Skidelsky writes Speech in the House of Lords Conduct Committee: Code of Conduct Review – 8th of October

Robert Skidelsky writes Britain’s Illusory Fiscal Black Hole

Matias Vernengo writes Argentina on the verge

In June this year, a company called intu (no capitalisation) collapsed. Most people had never heard of it. But they knew what it did. It was the owner of many of the UK's biggest shopping centres. Lakeside in Thurrock, Metro Centre in Newcastle, and the Trafford Centre in Manchester - all of these were owned by intu. Indeed, they still are. At the time of writing, no disposals have been made. So intu is the landlord of a significant part of the UK's retail sector. And it is dead, killed by the pandemic. But like many of those killed by the pandemic, intu had underlying health issues that made it especially vulnerable.

Long before the pandemic struck, the retail sector was in trouble. Over the last few years, a stream of household names have gone to the wall: Woolworths, Toys R Us, Mothercare, Maplin, BHS, Comet, and numerous fashion retailers. The department store House of Fraser was bought by Mike Ashley, owner of the lean and hungry Sports Direct. Numerous other retailers, such as the fashion chain Monsoon and the department store Debenhams, have entered into what is known as a "company voluntary arrangement" or CVA, under which the company's creditors agree to write down or reschedule its debts. One of the principal items that is typically reduced in a retail CVA is property rents.

It's normal for landlords to suffer a percentage of bad debts, and a prudent landlord will allow for this in their cash management. But what has been happening in the retail sector is far from a "normal" level of bankruptcies, defaults and debt reprofiling. And intu has been far from prudent. It has borrowed far too much and its cash flow is far from free. So although it was convenient for intu's management to blame the pandemic for its collapse, in fact it has been living on borrowed time. Structural changes in the retail sector which began long before the pandemic, though they were accelerated by it, made its eventual collapse inevitable. Even before the lockdown wrecked its balance sheet and destroyed its cash flows, intu was a zombie.

The statement from intu's administrators reveals that the proximate cause of intu's collapse was breach of a loan covenant on its revolving credit facility. The company had been advanced a line of credit by a bank which was similar to an overdraft or credit card: there was a fixed limit to the amount the company could borrow, but it didn't have to borrow the whole amount and it only paid interest on the amount borrowed. This facility was subject to certain conditions, known as "covenants": intu's covenants on its revolving credit facility included net worth and debt-to-net-worth limits. It is these covenants that were breached - with far-reaching consequences.

In its 2018 full-year accounts, intu reported a loss of some £1.1bn, principally due to revaluation of its property assets. The (then) Chief Executive, David Fischel, ruefully remarked that "After two years of essentially unchanged

valuations for our UK centres, 2018

saw investor sentiment turn against

retail property.

We reported a 6.2 per cent fall in property

values in the six months to 30 June 2018

and a further 3.0 per cent in the quarter

to 30 September 2018, with the full year

reduction in our assets amounting to

13.3 per cent." But he then cheerfully observed that property values would have to fall by quite a bit more for the company to breach its covenants:

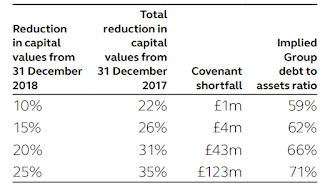

These facilities have significant covenant headroom. For example, a further fall of 10 per cent in capital values would create a covenant shortfall of only £1 million.

And he helpfully provided this table showing potential covenant shortfalls arising from properrty revaluations:

Fast forward to the 2019 full-year accounts, released in March 2019. The company reported a full-year loss of £2bn, of which £1.97bn was caused by a 22.3% downwards revaluation of its property portfolio. The company's asset base had shrunk by a third in two years.

It's not difficult to see why the value of intu's property portfolio fell so much, and so quickly. Financial markets, watching the bodies pile up in the retail sector, realised that the rentals gravy train on which commercial property returns depended was about to hit the buffers, and ran for the hills.

As CVAs and defaults rose, and vacancies increased, intu supported its income by extracting higher rents from its dwindling supply of solvent tenants. In 2019, it reported an uplift of 6% for existing rentals, well above inflation and of course wholly unsustainable. Despite this, income from rentals fell by 9%.

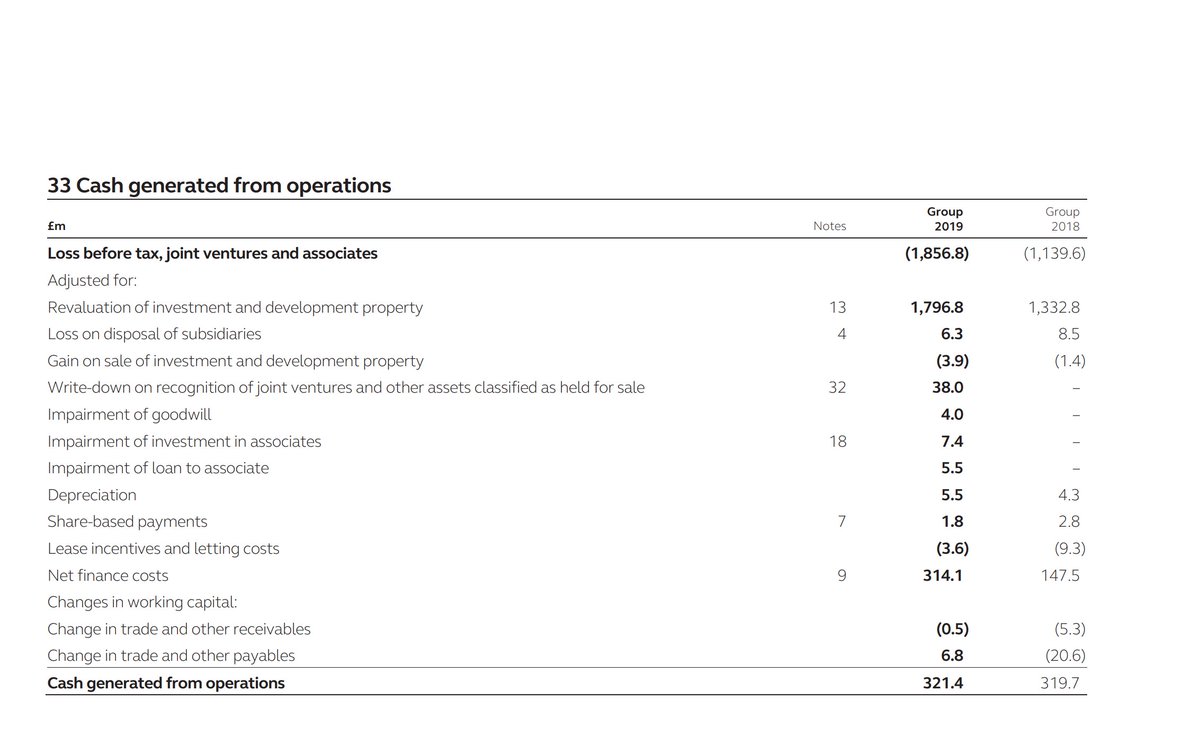

If intu's cash position had been stronger, it might have been able to ride out the property market turbulence. But its cash reserves were entirely borrowed. And note 33 to the company's 2019 full-year accounts reveals that its cash flow was on a knife edge:

|

Cash generated from operations was barely covering intu's finance costs. It wouldn't have taken much of a cash flow disruption for this to become ponzi financing. Servicing its £4.5bn net external debt was draining the company of cash.

The combination of rapid asset devaluation and declining income is fatal for a highly-indebted, cash-poor company like intu. Note 1 to the 2019 full-year accounts says that there was "material uncertainty" as to whether intu could continue as a going concern, and gives graphic details of the scale of the approaching disaster:

- A further fall of 10% in property values would result in covenant breaches costing £174m to resolve, including repayment of the £161m drawn balance on the revolving credit facility.

- A further decline of 10% in rental income would cost an additional £34m in debt service covenant breaches.

- £331.5m of repayments would fall due on 31 March 2021 and £1,116.7m on 31 December 2021, including £573.2m outstanding under the revolving credit facility

- Early termination of swaps could cost another £93m

This would not be remotely affordable. To have any hope of surviving, the company had to deleverage, and fast. The board identified a range of desperate measures:

- "alternative capital structures", probably involving some kind of debt/equity conversion, and possibly a rights issue

- fire sales of assets

- persuading lenders to waive or amend the covenants (the note says this would have to be done before the next covenant test, due in July 2020)

- "other self-help measures", including a lower level of capital expenditure "in the short term". This seems to be very much a last resort, probably because capital projects can be very costly to defer.

The external auditors called in their restructuring specialists to evaluate the reasonableness of these measures. They seem to have been distinctly underwhelmed. Though they didn't explicitly say it, the tone of the auditors' statement in the 2019 full-year accounts (op.cit.) is much more "this company is bust" than "these measures might have legs".

So even before the pandemic, intu was broken. All the pandemic did was accelerate its demise.

The end came quickly. Collapsing property values due to the lockdown caused an overwhelming breach of the net worth covenants on the revolving credit facility. The company tried to negotiate a "standstill" with its bank - a grace period during which the bank would refrain from calling in the debt - in the hope that the disruption to its cash flow caused by the lockdown would pass. But the bank wasn't impressed:

Discussions have been ongoing with financial stakeholders to achieving standstill-based agreements. However, insufficient alignment and agreement in relation to the terms of such standstill-based agreements has been achieved with financial stakeholders ahead of the above deadline.

It's not generally in a bank's interests to pull the plug on a solvent business that is suffering short-term cash flow disruption due to an external shock, especially when the government has made it very clear that forbearance should be the name of the game. Intu wasn't actually insolvent before the pandemic, though it was teetering on the edge. And it did have a recovery plan, though admittedly a highly risky one. So why did the bank pull the plug?

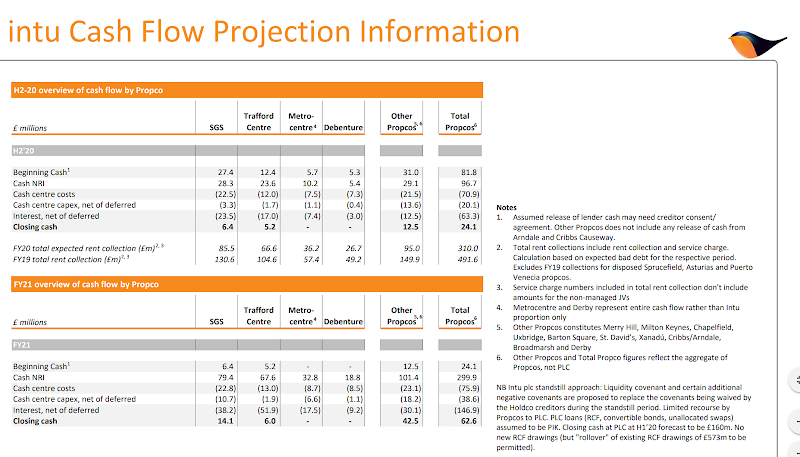

And here, I depart from the script. The company was in a horrible mess, but it was the effect of the pandemic that forced the bank to foreclose. The cash flow projections intu issued in June are disastrous:

(click here for larger version)

Not only does cash flow collapse in 2020 across all shopping centres, it doesn't fully recover in 2021. But intu was only just covering its debt service from existing cash flow, and it had £1.5bn of borrowing to refinance in 2021. No bank will lend to a company that is certain to default on its existing borrowing within a few months. Better to end it now than prolong the agony.

So what happens now? Well, intu is being run by administrators, whose job it is to find buyers, ideally for the whole company - though that seems unlikely in the present circumstances - or for parts of it. The shopping centres are still open, along with their shops. But because of the lockdown, many retailers are now unable to pay their rents. There is no possibility that intu's income will recover, and the value of its property portfolio is likely to continue to slide. It seems likely that it will eventually be broken up and the assets sold well below their book value. There will probably be job losses, though at the moment it is hard to say how many.

The demise of intu raises questions about the future of retail shopping. The pandemic, and associated lockdown, has accelerated migration not only to online shopping, but also to local shopping, since people have been actively discouraged from travelling. Will the footfall in shopping centres ever come back? Or are giant out-of-town shopping centres like big dinosaurs, slowly dying because the consumer climate is changing and they can't adapt? Is the pandemic their asteroid?

Related reading:

The key reasons why intu collapsed into administration - Nottingham Live

The sad story of Maplin Electronics

The sad story of Maplin Electronics

Aerial image of the Trafford Centre from Wikipedia.

.