Summary:

Hans Werner Sinn has apost on Project Syndicate which purports to explain why the plans of Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis are much cleverer than anyone has realised. I don’t disagree that Mr. Varoufakis’s plans are clever: indeed I have written several posts on Forbes explaining just how clever they are. But Professor Sinn’s explanation, sadly, is very wide of the mark. Here is Professor Sinn’s description of Mr. Varofakis’s strategy: Plan B comprises two key elements. First, there is simple provocation, aimed at riling up Greek citizens and thus escalating tensions between the country and its creditors. Greece’s citizens must believe that they are escaping grave injustice if they are to continue to trust their government during the difficult period that would follow an exit from the eurozone.Second, the Greek government is driving up the costs of Plan B for the other side, by allowing capital flight by its citizens. If it so chose, the government could contain this trend with a more conciliatory approach, or stop it outright with the introduction of capital controls. But doing so would weaken its negotiating position, and that is not an option.So Mr. Varoufakis’s strategy, apparently, is Grexit, for which he is preparing by stoking antagonism between Greece and its creditors while asset-stripping the rest of the EU. This is despite Mr.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: banks, ELA, EU, Eurozone, Germany, Greece, liquidity, Target2

This could be interesting, too:

Hans Werner Sinn has apost on Project Syndicate which purports to explain why the plans of Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis are much cleverer than anyone has realised. I don’t disagree that Mr. Varoufakis’s plans are clever: indeed I have written several posts on Forbes explaining just how clever they are. But Professor Sinn’s explanation, sadly, is very wide of the mark. Hans Werner Sinn has apost on Project Syndicate which purports to explain why the plans of Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis are much cleverer than anyone has realised. I don’t disagree that Mr. Varoufakis’s plans are clever: indeed I have written several posts on Forbes explaining just how clever they are. But Professor Sinn’s explanation, sadly, is very wide of the mark. Here is Professor Sinn’s description of Mr. Varofakis’s strategy: Plan B comprises two key elements. First, there is simple provocation, aimed at riling up Greek citizens and thus escalating tensions between the country and its creditors. Greece’s citizens must believe that they are escaping grave injustice if they are to continue to trust their government during the difficult period that would follow an exit from the eurozone.Second, the Greek government is driving up the costs of Plan B for the other side, by allowing capital flight by its citizens. If it so chose, the government could contain this trend with a more conciliatory approach, or stop it outright with the introduction of capital controls. But doing so would weaken its negotiating position, and that is not an option.So Mr. Varoufakis’s strategy, apparently, is Grexit, for which he is preparing by stoking antagonism between Greece and its creditors while asset-stripping the rest of the EU. This is despite Mr.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: banks, ELA, EU, Eurozone, Germany, Greece, liquidity, Target2

This could be interesting, too:

Merijn T. Knibbe writes ´Extra Unordinarily Persistent Large Otput Gaps´ (EU-PLOGs)

Merijn T. Knibbe writes In Greece, gross fixed investment still is at a pre-industrial level.

Michael Hudson writes All Of Our Wealth Has Been Coming From You

Bill Haskell writes FDIC: Number of Problem Banks Increased in Q1 2024

Here is Professor Sinn’s description of Mr. Varofakis’s strategy:

Plan B comprises two key elements. First, there is simple provocation, aimed at riling up Greek citizens and thus escalating tensions between the country and its creditors. Greece’s citizens must believe that they are escaping grave injustice if they are to continue to trust their government during the difficult period that would follow an exit from the eurozone.

Second, the Greek government is driving up the costs of Plan B for the other side, by allowing capital flight by its citizens. If it so chose, the government could contain this trend with a more conciliatory approach, or stop it outright with the introduction of capital controls. But doing so would weaken its negotiating position, and that is not an option.So Mr. Varoufakis’s strategy, apparently, is Grexit, for which he is preparing by stoking antagonism between Greece and its creditors while asset-stripping the rest of the EU. This is despite Mr. Varoufakis’s repeated statements of support for the EU and indeed for the Euro, which long pre-date his appointment as finance minister. What kind of turncoat does Professor Sinn think he is?

But let us assume for a minute that Professor Sinn is correct about Mr. Varoufakis’s intentions. Yes, Mr. Varoufakis’s statements have been inflammatory, and the effect has been to increase tension between Greece and its creditors. But what of Professor Sinn’s second statement – that Greece is deliberately encouraging capital flight in order to increase the costs of Grexit for the rest of Europe. How does this work?

Professor Sinn explains it thus:

Capital flight does not mean that capital is moving abroad in net terms, but rather that private capital is being turned into public capital. Basically, Greek citizens take out loans from local banks, funded largely by the Greek central bank, which acquires funds through the European Central Bank’s emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) scheme. They then transfer the money to other countries to purchase foreign assets (or redeem their debts), draining liquidity from their country’s banks.

Other eurozone central banks are thus forced to create new money to fulfill the payment orders for the Greek citizens, effectively giving the Greek central bank an overdraft credit, as measured by the so-called TARGET liabilities. In January and February, Greece’s TARGET debts increased by almost €1 billion ($1.1 billion) per day, owing to capital flight by Greek citizens and foreign investors. At the end of April, those debts amounted to €99 billion.

A Greek exit would not damage the accounts that its citizens have set up in other eurozone countries – let alone cause Greeks to lose the assets they have purchased with those accounts. But it would leave those countries’ central banks stuck with Greek citizens’ euro-denominated TARGET claims vis-à-vis Greece’s central bank, which would have assets denominated only in a restored drachma. Given the new currency’s inevitable devaluation, together with the fact that the Greek government does not have to backstop its central bank’s debt, a default depriving the other central banks of their claims would be all but certain.

A similar situation arises when Greek citizens withdraw cash from their accounts and hoard it in suitcases or take it abroad. If Greece abandoned the euro, a substantial share of these funds – which totaled €43 billion at the end of April – would flow into the rest of the eurozone, both to purchase goods and assets and to pay off debts, resulting in a net loss for the monetary union’s remaining members.This is an extraordinarily confused piece of writing.

Firstly, Professor Sinn asserts that Greeks are borrowing from Greek banks in order to transfer Euros out of Greece. On exit and redenomination the loans would be converted to drachma, which would promptly devalue leaving the Greek borrowers in possession of stashes of Euros for which they would now pay much less. It’s a plausible strategy, I suppose. There is only one problem with it. It isn’t happening.

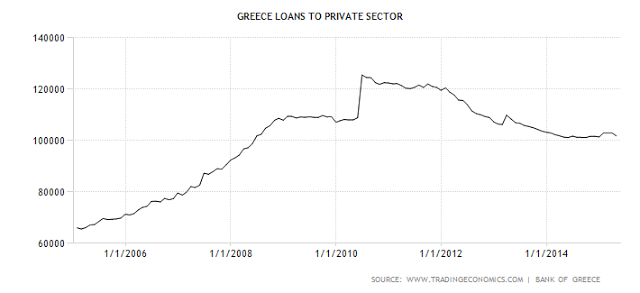

Private sector borrowing in Greece has actually been falling since 2010:

There was a tiny uptick in borrowing towards the end of 2014, no doubt because the prospects for the Greek economy looked brighter then. But the economy is now back in recession and lending has tailed off. The Bank of Greece’s figures show that private sector loans decreased by 1.2bn EUR in April. If there is capital flight going on, it isn’t funded by borrowing.

Professor Sinn also outlines an alternative: Greeks removing funds from banks and stashing them as physical cash. This is actually true. Demand for Euro notes & coins in Greece has soared and Greek mattresses have never been so stuffed. But why are Greeks doing this? After all, if they really want to move money out of Greece, by far the easiest way to do so is to open an account in, say, an Italian or Slovenian bank and electronically transfer the money there. Why are they removing funds from banks completely?

The answer has nothing to do with ELA, Target2 or the Greeks’ understandable desire to stiff the Germans. It is far simpler. Greece is very close to Cyprus, and the Greeks have not forgotten what happened there two years ago. They fear losing their deposits in order to bail out banks that are bankrupted by sudden removal of ELA. It is the ECB’s stranglehold on Greek bank liquidity that is driving their excessive demand for notes & coins.

In addition to conversion of deposits to physical cash, there has been a continual flow of deposits out of Greece since the beginning of the year. These are electronic transfers and they are almost certainly due to redenomination fears. For some reason Professor Sinn ignores these. Could it be that he does not understand - or chooses to deny – the purpose of the single currency? Or does he simply not understand modern electronic payments systems?

I suspect it is both. Let’s look at each in turn.

Firstly, the single currency. Free movement of capital within the EU is enshrined in treaty directives. Yes, capital controls were imposed in Cyprus to prevent capital flight after the banking system collapsed. But that was to ensure that the freeze on deposits in Cyprus’s broken banks held. Greek banks are wobbly, but they are still standing. Professor Sinn wishes Greece to impose capital controls not because its banks are broken, but simply because of the way the single currency works. Capital flight is supposed to happen in a monetary union: ordinary people and legitimate businesses should be able to move funds wherever they like and whenever they like within the union. Routinely interfering with this destroys the single currency.

Secondly, the payments mechanism. This is quite technical and I will have to do some accounting to explain how it all works. Basically, though, Sinn has confused the funding of banks with the movement of private sector deposits.

When a private sector agent makes a payment from a deposit account – whether that be to purchase goods or assets, withdraw physical cash or transfer funds elsewhere – the bank’s reserves reduce. To show this, let’s imagine that the customer is withdrawing physical cash. The accounting entries for the customer and his bank are as follows.

Customer: CR deposit account (asset)

DR back pocket (asset)

Bank: DR customer deposit account (liability)

CR reserves (asset)

For non-accountants, please note that a CR to an asset reduces it: DR increases it. I have preserved this convention even for customer cash movements where it is perhaps counter-intuitive, as in the example above. It will be very important to remember this as we go through the Target2 accounting later on.

The customer has simply exchanged one asset for another. But the bank actually has less money. This shows up as a reduction in reserves. Reserves are a form of “money” used only by banks among themselves. Their sole purpose is to facilitate movements in and out of customer deposit accounts. They are, in a word, “liquidity”.

If a lot of customers withdraw physical cash, or transfer funds to other banks, the bank can run out of reserves. Banks can borrow reserves from other banks by pledging assets as collateral, typically government debt. But if the bank can’t borrow reserves from other banks – and not many commercial banks will lend to Greek banks now, because who is going to accept Greek government debt as collateral? - it turns to its central bank. Explaining ELA

Central banks will lend reserves to banks against a range of collateral, subject to haircuts and conditions. In the Eurosystem, provision of “emergency liquidity assistance” (ELA) is the responsibility of national central banks, though it requires ECB approval.

ELA is provided to Greek banks by the Hellenic Central Bank, which bears all the risks associated with it. Professor Sinn’s assertion that the risks of lending rebound to other central banks in the Eurosystem is flatly contradicted by the ECB:

ELA means the provision by a Eurosystem national central bank (NCB) of:In the event of Greek default, the Hellenic National Bank would become technically insolvent because of all the Greek sovereign debt that has been pledged to it by Greek banks. But it would be the responsibility of the Greek sovereign to recapitalise it, not other central banks.

(a) central bank money and/or

(b) any other assistance that may lead to an increase in central bank money to a solvent financial institution, or group of solvent financial institutions, that is facing temporary liquidity problems, without such operation being part of the single monetary policy. Responsibility for the provision of ELA lies with the NCB(s) concerned. This means that any costs of, and the risks arising from, the provision of ELA are incurred by the relevant NCB.

If Greece defaulted and left the Euro, the Hellenic National Bank would acquire the right to create the new national currency – a right it does not currently possess. Greek government debt, we assume, would be redenominated in the new currency (lex monetae). Grexit, therefore, would resolve the Hellenic National Bank’s “insolvency”. However, that would create a problem. What would it do with the Euro-denominated reserves on its balance sheet?

The simple answer is that it would also convert those to drachma. Greek banks would then be unable to meet demands for Euro deposit account withdrawals. Greece would have no choice but to impose capital controls and a bank holiday to avoid bankrupting the banks.

But the conversion of both Euro-denominated reserves and their collateral (Greek sovereign debt) to drachma would have no effect whatsoever on other central banks. There would be no losses anywhere else in the Eurozone. Sinn is simply wrong about ELA.

But what about Target2?

The question of Target2 balances is somewhat more complex. Target2 is the Eurosystem’s real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system. All Western central banks have RTGS systems: they are the core of the electronic payments systems upon which Westerners have come to depend. Target2 is a little more complex than the RTGS of a single country such as the UK.

But only a little more complex. It is in reality far more straightforward than a lot of the rubbish that is written about it suggests.

Example 1: How asymmetric trade flows cause Target2 imbalances

The Bank of England’s RTGS system can settle payments between people in London and people in Manchester. If people in Manchester make lots of purchases from companies based in London, funds flow from Manchester to London. But we use double entry accounting to record all movements of funds. So a net flow of say £1m private sector funds from Manchester to London through the Bank of England’s RTGS system looks like this:

Manchester private sector CR cash at bank £1,000,000 (asset) DR e.g. fixed assets £1,000,000 (asset)

Manchester banks DR customer deposits £1,000,000 (liability) CR reserves £1,000,000 (asset)

London banks CR customer deposits £1,000,000 (liability) DR reserves £1,000,000 (asset)

London private sector DR cash at bank £1,000,000 (asset) CR inventory £1,000,000 (asset)

This is what is known as “quadruple accounting”, where double entries are recorded for all four participants. You can see that there has been a movement of goods (fixed assets) from London to Manchester. You can also see that there has been a movement of cash from banks in Manchester to banks in London, which is recorded both as a change in “cash at bank” on the customer side and as a change in “customer deposits” at the banks. This is NOT two lots of money: it is the same money, recorded as an asset & liability pair (customer asset, bank liability). You can also see that there has been a movement of reserves from banks in Manchester to banks in London (remember CR to a bank’s reserve account reduces the balance).

Now let’s add in the central bank’s reserve accounts. Remember that reserves are assets for commercial banks. The corresponding liabilities are held at the central bank. We can think of reserve accounts at the central bank as similar to a bank customer’s transaction account: it contains a small amount of moving funds. So when there is a net flow of funds from Manchester to London, the reserve movements look like this:

Bank reserve accounts (assets):

Manchester banks CR £1,000,000

London banks DR £1,000,000

Central bank reserve accounts (liabilities):

Manchester DR £1,000,000

London CR £1,000,000

So at the central bank there is a reserve imbalance between Manchester and London. Manchester is in “deficit” and London is in “surplus”. Or, putting it another way, Manchester has a net liability to the central bank and London has a net claim on it. As the entries balance, we could ignore the central bank completely and say that London has a net claim on Manchester.

But this is silly. London’s private sector has already received cash. All the reserve entries show is that there has been a net flow of funds from Manchester to London. In this case it is balanced by a net flow of goods in the other direction. What this is showing, therefore, is that London has a trade surplus and Manchester a trade deficit. In no sense does Manchester “owe” London anything. It has already paid.

Now, using the above example, replace Manchester with Greece, London with Germany, and the Bank of England with the ECB. All Target2 does is facilitate and record these movements of funds. It is a gross misunderstanding of RTGS settlement accounting to describe the imbalances arising from these movements as “debts”, as Professor Sinn does.

So we can see clearly how Target2 records the trade imbalance between Germany and Greece. But there was a large trade imbalance between Germany and Greece before the financial crisis. Why did this not show up as a Target2 imbalance?

The reason is that prior to the financial crisis, Greece’s trade deficit with Germany was funded by borrowing from German banks. Let me show you how this works.

Example 2: How foreign financing of trade deficits eliminates Target2 imbalances

Greek customer takes out a loan of 1,000,000m EUR from a German bank (in practice this was often mercantile credit, i.e. importer borrowed from exporter who in turn borrowed from his own local bank, but let’s not complicate things). The loan accounting entries are as follows:

Greek customer CR German bank loan 1,000,000 (liability) DR cash at German bank 1,000,000 (asset)

German bank DR Greek customer loan account 1,000,000 (asset) CR Greek customer deposit account 1,000,000 (liability)

The Greek customer pays the money to the German exporter. The accounting entries are as follows:

Greek customer DR goods & services received 1,000,000 (asset) CR cash at German bank 1,000,000 (asset)

German exporter CR inventory 1,000,000 (asset) DR cash at bank 1,000,000 (asset)

German banks (aggregate) DR Greek customer deposit account 1,000,000 (liability)

CR German exporter deposit acct 1,000,000 (liability)

RTGS reserve accounts (liability):

DR Germany 1,000,000

CR Germany 1,000,000

In other words, although the customer is Greek, the financial transaction in effect takes place entirely within Germany. This is why there were no Target2 imbalances even though Greece had a large trade deficit with Germany.

When the Greek crisis hit, German banks stopped financing German exports to Greece. Greek customers were forced to borrow from Greek banks instead (you can see this clearly as a spike in Greek bank lending in early 2010 in the chart above). The result was a large Target2 imbalance.

But as the Greek economy faltered, imports to Greece fell massively. Trade stopped being the main cause of the Target2 imbalance. What replaced it was capital flight. And it is capital flight, not trade, that is currently causing the Target2 imbalance to grow.

Example 3: How capital flight exacerbates Target2 imbalances

Suppose we have a Greek who has £1mEUR of cash deposits at Greek banks. Fearing capital controls, redenomination and seizure of his deposits, he decides to move his money to safety in Germany. So he opens a deposit account at a German bank and transfers his money electronically from his Greek bank deposits to the German bank. The accounting entries look like this.

Greek customer CR Greek bank deposits 1,000,000 (asset)

DR German bank deposit 1,000,000 (asset)

Greek bank DR customer deposits 1,000,000 (liability)

CR reserves 1,000,000 (asset)

German bank CR customer deposits 1,000,000 (liability)

DR reserves 1,000,000 (liability)

RTGS reserve accounts (liability):

Greece DR 1,000,000

Germany CR 1,000,000

The Greek customer’s decision to move his money to safety widens the Target2 imbalance.

Because Professor Sinn believes that Target2 “deficits” are actual debts, and Greece is already very highly indebted, he thinks that Greece should take steps to stop the Target2 imbalances increasing. Greece should therefore impose capital controls so that our Greek customer can’t move his money to safety outside Greece. Presumably Professor Sinn also thinks that Greece should eliminate its trade deficit, though he doesn’t say this.

Central banks do not allow banks to run persistent reserve account deficits. Greek banks experiencing capital flight therefore have to borrow reserves to top up their reserve accounts. At present, because no-one else will lend to them, they borrow reserves from the Hellenic Central Bank, as I explained above. The Hellenic Central Bank’s balance sheet is therefore expanding by an amount corresponding to the growth of Greece’s Target2 deficit. But that does not mean they are the same thing. Professor Sinn unfortunately confuses them.

How would Grexit affect Target2?

Much time and energy has been spent discussing what the effect on Target2 – and, by extension, the ECB – would be if Greece left the Euro. Unfortunately most of the explanations are wrong.

Currently, Greece is running a Target2 deficit which is entirely covered, as far as Greek banks are concerned, by ELA from the Hellenic Central Bank. Suppose that Greece defaults, creates a new currency and redenominates all sovereign debt and all bank reserves into drachma, including reserves created through ELA. What does this do to Target2?

Nothing. Nothing at all. Zilch. Nada. Nix.

The Target2 “deficit” would remain as a notional liability of the newly-independent Greek state. It would still be denominated in Euros, since Greece would have no power to redenominate it. It would be frozen, since Greek capital controls and suspension of external trade in Euros would mean no further Target2 transactions. It would not need to be settled, paid, reallocated or otherwise disposed of. It could simply be ignored.

“But”, I hear you say, “surely there’s a catch?”

There is no catch. The existing Target2 deficit for Greece is entirely balanced by payments already made from Greek banks to banks elsewhere in the Eurozone. No-one is going to lose any money if Greece stops using Target2 because it ditches the Euro.

I admit, it has taken me quite a while to "get" this, despite the promptings of my good friend Beate Reszat who has always insisted that Target2 is simply a "black box" computer system and has nothing whatsoever to do with national accounting. But having now worked through the accounting, I am sure of my ground. The whole Target2 imbalances issue is a complete red herring.

If someone felt like being tidy, they could simply eliminate Greece’s notional Target2 deficit by proportionately reducing the Target2 surpluses of its Eurozone trade partners. In fact as the balancing reserves in Greek banks would already have been redenominated into drachma, this would technically be the correct thing to do. The Hellenic Central Bank leaving the Eurosystem and redenominating Greek bank reserves into drachma would reduce the aggregate quantity of Euro-denominated reserves in the Eurosystem. Bringing Target2 into line with this would preserve the consistency of Target2 balances with Eurosystem reserves. But it isn’t strictly necessary.

Nor is Greek redenomination potentially inflationary for the rest of the Eurozone, as some have suggested. Rather the reverse, actually. Capital flight can be inflationary for “safe haven” countries. If Greece left the Eurozone, capital flight would stop due to capital controls. This would be deflationary for the rest of the Eurozone, not inflationary.

Once the dust had settled, of course, Greece would want to lift capital controls and start trading with the Eurozone again. Most trade would probably be in Euros and settled via Target2. But that is true for any non-Eurozone country trading in Euros with the Eurozone. The Euro would be a foreign currency for Greece. It would have to earn euros through trade. And because of this, it would need to run a substantial trade surplus, helped by inevitable devaluation of the drachma. So if it were not “tidied up”, Greece’s Target2 deficit would shrink over time.

To sum up, Professor Sinn’s piece is wrong from beginning to end. Sadly, because there is so little general understanding of what is a pretty technical subject, and he is one of the few people paying attention to Target2, he is widely believed. Even Wolfgang Munchau, who should know better, was convinced. I despair, I really do.